Il testo di logica filosofica che storicamente fu il fondamento dell'epistemologia cibernetica è Le Leggi della Forma - Laws of Form di G. Spencer-Brown, pubblicato per la prima volta nel 1969. Brown è un personaggio che si è sempre circondato da un alone di mistero, è ritenuto un esperto eclettico in varie discipline (polymath), ha frequentato e studiato con personaggi quali Russell, Wittgenstein e Laing ed ha fortemente influenzato con il suo lavoro molti autori del movimento sistemico-cibernetico come Von Foerster, Maturana, Varela, Kauffman e lo stesso Bateson. Egli è anche, ad esempio, il romanziere James Keys con la sua visione mistica dei "cinque livelli di eternità":

Un aneddoto di Bateson su un suo incontro con Spencer-Brown insieme a Heinz Von Foerster, citato da Keeney (1977), dimostra come Brown tenda a mantenere ignoto il suo territorio:

La mattina in cui dovevo incontrare Brown parlai con Von Foerster per vedere se avevo colpito nel segno. Gli dissi che i simboli a forma di L rovesciata erano una sorta di negazione ... Mi rispose "Lo hai capito Gregory". In quel momento Brown entrò nella stanza e Heinz gli disse: "Gregory lo ha capito - quelle cose sono una sorta di negazione". E Brown rispose: "Non è vero!".

G. Bateson, cit. in Keeney, "L'estetica del cambiamento", 1985

Von Foerster associava Spencer-Brown, Wittgenstein (di cui era il nipote) e Don Juan, il maestro yaqui narrato da Carlos Castaneda, per la loro aria melanconica di chi "sa di sapere".

(*): si ha ragione di credere che Spencer-Brown sia figlio unico.

The position is simply this. In ordinary algebra, complex values are accepted as a matter of course, and the more advanced techniques would be impossible without them. In Boolean algebra (and thus, for example, in all our reasoning processes) we disallow them. Whitehead and Russell introduced a special rule, which they called the Theory of Types, expressly to do so. Mistakenly, as it now turns out. So, in this field, the more advanced techniques, although not impossible, simply don't yet exist. At the present moment we are constrained, in our reasoning processes, to do it the way it was done in Aristotle's day. The poet Blake might have had some insight into this, for in 1788 he wrote that 'reason, or the ratio of all we have already known, is not the same that it shall be when we know more.'

Recalling Russell's connexion with the Theory of Types, it was with some trepidation that I approached him in 1967 with the proof that it was unnecessary. To my relief he was delighted. The Theory was, he said, the most arbitrary thing he and Whitehead had ever had to do, not really a theory but a stopgap, and he was glad to have lived long enough to see the matter resolved.

Put as simply as I can make it, the resolution is as follows. All we have to show is that the self-referential paradoxes, discarded with the Theory of Types, are no worse than similar self-referential paradoxes, which are considered quite acceptable, in the ordinary theory of equations.

The most famous such paradox in logic is in the statement, 'This statement is false.'

Suppose we assume that a statement falls into one of three categories, true, false, or meaningless, and that a meaningful statement that is not true must be false, and one that is not false must be true. The statement under consideration does not appear to be meaningless (some philosophers have claimed that it is, but it is easy to refute this), so it must be true or false. If it is true, it must be, as it says, false. But if it is false, since this is what it says, it must be true.

It has not hitherto been noticed that we have an equally vicious paradox in ordinary equation theory, because we have carefully guarded ourselves against expressing it this way. Let us now do so.

We will make assumptions analogous to those above. We assume that a number can be either positive, negative, or zero. We assume further that a nonzero number that is not positive must be negative, and one that is not negative must be positive.

We now consider the equation

Mere inspection shows us that x must be a form of unity, or the equation would not balance numerically. We have assumed only two forms of unity, +1 and — 1, so we may now try them each in turn. Set x = +1. This gives

We take as given the idea of distinction and the idea of indication, and that we cannot make an indication without drawing a distinction. We take, therefore, the form of distinction for the form.

Definition

Distinction is perfect continence.

That is to say, a distinction is drawn by arranging a boundary with separate sides so that a point on one side cannot reach the other side without crossing the boundary. For example,in a plane space a circle draws a distinction.

Once a distinction is drawn, the spaces, states, or contents on each side of the boundary, being distinct, can be indicated.

There can be no distinction without motive, and there can be no motive unless contents are seen to differ in value.

If a content is of value, a name can be taken to indicate this value.

Thus the calling of the name can be identified with the value of the content.

Axiom 1. The law of calling

The value of a call made again is the value of the call.

Content

Call it the first distinction.

Call the space in which it is drawn the space severed or cloven by the distinction.

Call the parts of the space shaped by the severance or cleft the sides of the distinction or, alternatively, the spaces, states,or contents distinguished by the distinction.

Intent

Let any mark, token, or sign be taken in any way with or with regard to the distinction as a signal.

Call the use of any signal its intent.

L'operatore di segno (mark o cross):

Un aneddoto di Bateson su un suo incontro con Spencer-Brown insieme a Heinz Von Foerster, citato da Keeney (1977), dimostra come Brown tenda a mantenere ignoto il suo territorio:

La mattina in cui dovevo incontrare Brown parlai con Von Foerster per vedere se avevo colpito nel segno. Gli dissi che i simboli a forma di L rovesciata erano una sorta di negazione ... Mi rispose "Lo hai capito Gregory". In quel momento Brown entrò nella stanza e Heinz gli disse: "Gregory lo ha capito - quelle cose sono una sorta di negazione". E Brown rispose: "Non è vero!".

G. Bateson, cit. in Keeney, "L'estetica del cambiamento", 1985

|

Von Foerster associava Spencer-Brown, Wittgenstein (di cui era il nipote) e Don Juan, il maestro yaqui narrato da Carlos Castaneda, per la loro aria melanconica di chi "sa di sapere".

La base storico-logica del testo di Brown è il superamento della logica classica (o aristotelica) che la monumentale opera di Russell e Whitehead Principia Mathematica del 1910 cercava di preservare contro i paradossi matematici, e che fu dimostrato impossibile nel 1931 dai teoremi di incompletezza di Gödel. Dal 1931 ogni tipo di logica formale deve esplicitamente tenere conto dell'esistenza dei paradossi logici dato che, come dimostrato da Gödel, in ogni sistema formale sufficientemente "potente" - come l'aritmetica - si possono derivare proposizioni indecidibili, che non sono né vere né false ma paradossali: se sono vere allora sono false e viceversa.

Come scrive Brown nella prefazione:

La teoria dei tipi logici, benchè confutata in logica formale dal lavoro di Gödel, ha definito il concetto fondamentale di livello logico di tipo meta-, applicato da Bateson nei modelli sull'interazione e comunicazione umana e animale, e fondamentale per definire meta-classi, meta-termini, meta-descrizioni e meta-spiegazioni in teoria della complessità.

Come scrive Brown nella prefazione:

Ricordando la connessione di Russell con la Teoria dei Tipi, è con una certa trepidazione che mi avvicinai a lui nel 1967 con la prova che non era necessaria. Con mio grande sollievo ne fu felice. La teoria è stata, ha detto, la cosa più arbitraria che lui e Whitehead avevano mai avuto a che fare, non proprio una teoria, ma un palliativo, ed era felice di aver vissuto abbastanza a lungo per vedere la soluzione del problema.

La teoria dei tipi logici, benchè confutata in logica formale dal lavoro di Gödel, ha definito il concetto fondamentale di livello logico di tipo meta-, applicato da Bateson nei modelli sull'interazione e comunicazione umana e animale, e fondamentale per definire meta-classi, meta-termini, meta-descrizioni e meta-spiegazioni in teoria della complessità.

Il tema è presentato da Brown nella sua prefazione:

PREFAZIONE ALLA PRIMA EDIZIONE AMERICANA

Oltre ai normali problemi logici universitari, che il calcolo pubblicato in questo testo rende così facili che non dobbiamo preoccuparci oltre, forse la cosa più significativa, dal punto di vista matematico, è che ci permette di utilizzare valori complessi nell'algebra della logica. Sono gli analoghi, in algebra ordinaria, dei numeri complessi a+b√-1. Io e mio fratello(*) abbiamo usato le loro controparti booleane in ingegneria pratica per diversi anni prima di capire cosa fossero. Naturalmente, essendo quello che sono, funzionano perfettamente, ma, comprensibilmente, ci siamo sentiti un po in colpa per il loro utilizzo, così come i primi matematici ad utilizzare "radici quadrate di numeri negativi" si sono sentiti in colpa, perché anche loro non potevano vedere alcun modo plausibile di dare loro un senso accademico rispettabile . Ad ogni modo, eravamo abbastanza sicuri che ci fosse una teoria perfettamente buona che li supporta, se solo potessimo pensarci.

La posizione è semplicemente questa. In algebra ordinaria, valori complessi sono accettati come una cosa naturale, e le tecniche più avanzate sarebbero impossibile senza di loro. In algebra booleana (e quindi, per esempio, in tutti i nostri processi di ragionamento) li abbiamo impediti. Whitehead e Russell hanno introdotto una norma speciale, che hanno chiamato la Teoria dei Tipi, espressamente per farlo. Erroneamente, a quanto pare ora. Quindi, in questo campo, le tecniche più avanzate, anche se non impossibili, semplicemente non esistono ancora. Al momento attuale siamo costretti, nei nostri processi di ragionamento, a farlo nel modo in cui era fatto ai tempi di Aristotele. Il poeta Blake avrebbe potuto avere una certa comprensione di questo, perché nel 1788 scrisse che 'la ragione, o del rapporto tra tutto quello che abbiamo già conosciuto, non è la stessa che deve essere quando ne sapremo di più.'

Ricordando la connessione di Russell con la Teoria dei Tipi, è con una certa trepidazione che mi avvicinai a lui nel 1967 con la prova che non era necessaria. Con mio grande sollievo ne fu felice. La teoria è stata, ha detto, la cosa più arbitraria che lui e Whitehead avevano mai avuto a che fare, non proprio una teoria, ma un palliativo, ed era felice di aver vissuto abbastanza a lungo per vedere la soluzione del problema.

Mettendola nel modo più semplice che si può, la risoluzione è la seguente. Tutto quello che dobbiamo dimostrare è che i paradossi auto-referenziali, scartati con la Teoria dei Tipi, non sono peggio di paradossi auto-referenziali simili, che sono considerati abbastanza accettabili, nell'ordinaria teoria delle equazioni.

Il paradosso più famoso in logica è nella dichiarazione, 'Questa affermazione è falsa.'

Supponiamo di supporre che una dichiarazione rientra in una delle tre categorie, vero, falso, o privo di significato, e che una dichiarazione significativa che non è vera deve essere falsa, e una che non è falsa deve essere vera. La dichiarazione in questione non sembra essere priva di senso (alcuni filosofi hanno sostenuto che lo è, ma è facile confutarlo), quindi deve essere vera o falsa. Se è vera, deve essere, come dice, falsa. Ma se è falsa, poiché questo è quello che dice, deve essere vera.

Non è stato finora notato che abbiamo un paradosso altrettanto vizioso nella teoria delle equazioni ordinarie, perché abbiamo ci siamo accuratamente guardati dall'esprimendo in questo modo. Vediamo ora di farlo.

Faremo ipotesi analoghe a quelle di cui sopra. Partiamo dal presupposto che un numero può essere sia positivo, negativo o zero. Si assume inoltre che un numero diverso da zero che non è positivo deve essere negativo, e uno che non è negativo deve essere positivo.

Consideriamo ora l'equazione

x2+1=0

Trasponendo, abbiamo

x2=-1

e dividendo entrambi i membri per x si ha,

x = -1/x

Possiamo vedere che questo (come la dichiarazione analoga in logica) è auto-referenziale: la radice-valore di x che cerchiamo deve essere riintrodotta nell'espressione da cui la cerchiamo.

Un semplice esame ci mostra che x deve essere una forma di unità, o l'equazione non sarebbe bilanciata numericamente. Abbiamo assunto solo due forme di unità, +1 e -1, quindi possiamo ora provare a turno. Imponiamo x = 1. Questo dà

+ 1 = -1 / +1 = - 1

che è chiaramente paradossale. Quindi impostiamo x = -1. Questa volta abbiamo

- 1 = -1/-1 = + 1

ed è altrettanto paradossale.

Naturalmente, come tutti sanno, il paradosso in questo caso viene risolto con l'introduzione di una quarta classe di numeri, chiamati immaginari, in modo da poter dire che le radici della equazione di cui sopra sono ± i, dove i è un nuovo tipo di unità che consiste di una radice quadrata di meno uno.

...

G SPENCER-BROWN

Cambridge, Inghilterra

Giovedì Santo 1972

(*): si ha ragione di credere che Spencer-Brown sia figlio unico.

PREFACE TO THE FIRST AMERICAN EDITION

Apart from the standard university logic problems, which the calculus published in this text renders so easy that we need not trouble ourselves further with them, perhaps the most significant thing, from the mathematical angle, that it enables us to do is to use complex values in the algebra of logic. They are the analogs, in ordinary algebra, to complex numbers a + b √- 1 . My brother and I had been using their Boolean counterparts in practical engineering for several years before realizing what they were. Of course, being what they are, they work perfectly well, but understandably we felt a bit guilty about using them, just as the first mathematicians to use 'square roots of negative numbers' had felt guilty, because they too could see no plausible way of giving them a respectable academic meaning. All the same, we were quite sure there was a perfectly good theory that would support them, if only we could think of it.

The position is simply this. In ordinary algebra, complex values are accepted as a matter of course, and the more advanced techniques would be impossible without them. In Boolean algebra (and thus, for example, in all our reasoning processes) we disallow them. Whitehead and Russell introduced a special rule, which they called the Theory of Types, expressly to do so. Mistakenly, as it now turns out. So, in this field, the more advanced techniques, although not impossible, simply don't yet exist. At the present moment we are constrained, in our reasoning processes, to do it the way it was done in Aristotle's day. The poet Blake might have had some insight into this, for in 1788 he wrote that 'reason, or the ratio of all we have already known, is not the same that it shall be when we know more.'

Recalling Russell's connexion with the Theory of Types, it was with some trepidation that I approached him in 1967 with the proof that it was unnecessary. To my relief he was delighted. The Theory was, he said, the most arbitrary thing he and Whitehead had ever had to do, not really a theory but a stopgap, and he was glad to have lived long enough to see the matter resolved.

Put as simply as I can make it, the resolution is as follows. All we have to show is that the self-referential paradoxes, discarded with the Theory of Types, are no worse than similar self-referential paradoxes, which are considered quite acceptable, in the ordinary theory of equations.

The most famous such paradox in logic is in the statement, 'This statement is false.'

Suppose we assume that a statement falls into one of three categories, true, false, or meaningless, and that a meaningful statement that is not true must be false, and one that is not false must be true. The statement under consideration does not appear to be meaningless (some philosophers have claimed that it is, but it is easy to refute this), so it must be true or false. If it is true, it must be, as it says, false. But if it is false, since this is what it says, it must be true.

It has not hitherto been noticed that we have an equally vicious paradox in ordinary equation theory, because we have carefully guarded ourselves against expressing it this way. Let us now do so.

We will make assumptions analogous to those above. We assume that a number can be either positive, negative, or zero. We assume further that a nonzero number that is not positive must be negative, and one that is not negative must be positive.

We now consider the equation

x2+1=0

Transposing, we have

x2=-1

and dividing both sides by x gives ,

x=-1/x

We can see that this (like the analogous statement in logic) is self-referential: the root-value of x that we seek must be put back into the expression from which we seek it.

Mere inspection shows us that x must be a form of unity, or the equation would not balance numerically. We have assumed only two forms of unity, +1 and — 1, so we may now try them each in turn. Set x = +1. This gives

+ 1= -1/+1= - 1

which is clearly paradoxical. So set x= -1. This time we have

- 1= -1/-1= + 1

and it is equally paradoxical.

Of course, as everybody knows, the paradox in this case is resolved by introducing a fourth class of number, called imaginary, so that we can say the roots of the equation above are ± i, where i is a new kind of unity that consists of a square root of minus one.

Of course, as everybody knows, the paradox in this case is resolved by introducing a fourth class of number, called imaginary, so that we can say the roots of the equation above are ± i, where i is a new kind of unity that consists of a square root of minus one.

...

G SPENCER-BROWN

Cambridge, England

Maundy Thursday 1972

Maundy Thursday 1972

L'epistemologia di Brown è esplicitamente dichiarata all'inizio del testo:

UNA NOTA SUL METODO MATEMATICO

Il tema di questo libro è che un universo viene in essere quando uno spazio viene separato o reciso. La pelle di un organismo vivente taglia un fuori da un dentro. Così fa la circonferenza di un cerchio in un piano. Tracciando il nostro modo di rappresentare una separazione, possiamo cominciare a ricostruire, con una precisione e una copertura che appaiono quasi inquietanti, le forme fondamentali alla base della scienza linguistica, matematica, fisica e biologica, e si può cominciare a vedere come le leggi familiari della nostra esperienza seguono inesorabilmente dall'atto originale di separazione.

L'atto in se stesso è già ricordato, anche se inconsciamente, come il nostro primo tentativo di distinguere le cose diverse in un mondo dove, in primo luogo, i confini si possono tracciare ovunque vogliamo. In questa fase l'universo non può essere distinto dal nostro modo di agire su di esso, e il mondo può sembrare come sabbie mobili sotto i nostri piedi.

Sebbene tutte le forme, e quindi tutti gli universi, sono possibili, e ogni particolare forma è mutevole, diventa evidente che le leggi riguardanti tali forme sono le stesse in qualsiasi universo. E questa uniformità, l'idea che possiamo trovare una realtà che è indipendente da come l'universo effettivamente appare, che conferisce un tale fascino allo studio della matematica. Che la matematica, in comune con altre forme d'arte, può condurci al di là dell'esistenza ordinaria, e ci può mostrare qualcosa della struttura in cui tutta la creazione si unisce insieme, non è un'idea nuova. Ma testi matematici in genere iniziano la storia da qualche parte nel mezzo, lasciando al lettore di riprendere il filo come meglio può. Qui la storia è tracciata fin dall'inizio.

A differenza di forme più superficiali di competenza, la matematica è un modo di dire sempre meno circa sempre di più. Un testo matematico non è dunque fine a se stesso, ma una chiave per un mondo oltre l'ambito della descrizione ordinaria.

Un'esplorazione iniziale di un tale mondo è di solito effettuata in compagnia di una guida esperta. Intraprenderla da solo, sebbene possibile, è forse difficile come entrare nel mondo della musica tentando, senza una guida personale, di leggere i fogli di un maestro compositore, o di preparare un primo volo personale su un aeroplano senza nessuna preparazione diversa da quella dello studio del manuale del pilota.

A NOTE ON THE MATHEMATICAL APPROACH

The theme of this book is that a universe comes into being when a space is severed or taken apart. The skin of a living organism cuts off an outside from an inside. So does the circumference of a circle in a plane. By tracing the way we represent such a severance, we can begin to reconstruct, with an accuracy and coverage that appear almost uncanny, the basic forms underlying linguistic, mathematical, physical, and biological science, and can begin to see how the familiar laws of our own experience follow inexorably from the original act of severance.

The act is itself already remembered, even if unconsciously, as our first attempt to distinguish different things in a world where, in the first place, the boundaries can be drawn anywhere we please. At this stage the universe cannot be distinguished from how we act upon it, and the world may seem like shifting sand beneath our feet.

The act is itself already remembered, even if unconsciously, as our first attempt to distinguish different things in a world where, in the first place, the boundaries can be drawn anywhere we please. At this stage the universe cannot be distinguished from how we act upon it, and the world may seem like shifting sand beneath our feet.

Although all forms, and thus all universes, are possible, and any particular form is mutable, it becomes evident that the laws relating such forms are the same in any universe. It is this sameness, the idea that we can find a reality which is independent of how the universe actually appears, that lends such fascination to the study of mathematics. That mathematics, in common with other art forms, can lead us beyond ordinary existence, and can show us something of the structure in which all creation hangs together, is no new idea. But mathematical texts generally begin the story somewhere in the middle, leaving the reader to pick up the thread as best he can. Here the story is traced from the beginning.

Unlike more superficial forms of expertise, mathematics is a way of saying less and less about more and more. A mathematical text is thus not an end in itself, but a key to a world beyond the compass of ordinary description.

An initial exploration of such a world is usually undertaken in the company of an experienced guide. To undertake it alone, although possible, is perhaps as difficult as to enter the world of music by attempting, without personal guidance, to read the score-sheets of a master composer, or to set out on a first solo flight in an aeroplane with no other preparation than a study of the pilots' manual.

Nella prima parte Brown delinea cosa sia una forma:

L A F O R M A

Diamo per scontato l'idea di distinzione e l'idea di indicazione, e che non possiamo fare una indicazione senza operare una distinzione. Prendiamo, quindi, la forma di distinzione per la forma.

Definizione

Distinzione è perfetta continenza.

Vale a dire, viene fatta una distinzione disponendo un confine con lati separati in modo che un punto su un lato non può raggiungere il lato senza attraversare il confine. Ad esempio, in uno spazio piano un cerchio opera una distinzione.

Una volta che si è operata una distinzione, gli spazi, stati o contenuti su ciascun lato del confine, essendo distinti, possono essere indicati.

Non ci può essere alcuna distinzione, senza motivo, e non può esserci nessun motivo a meno che i contenuti sono visti differire in valore.

Se un contenuto è di valore, un nome può essere assunto per indicare questo valore.

Così la chiamata del nome può essere identificata con il valore del contenuto.

Assioma 1. La legge di chiamata

Il valore di una chiamata effettuata di nuovo è il valore della chiamata.

Cioè, se un nome viene chiamato e poi viene chiamato nuovamente, il valore indicato dalle due chiamate prese insieme è il valore indicato da uno di essi.

Vale a dire, per ogni nome, richiamare è chiamare.

Allo stesso modo, se il contenuto è di valore, un motivo o intenzione o istruzione di attraversare entro il confine nel contenuto può essere assunto per indicare questo valore.

Pertanto, anche, l'attraversamento del limite può essere identificato con il valore del contenuto.

Assioma 2. La legge di attraversamento

Il valore di un attraversamento fatta di nuovo non è il valore dell'attraversamento.

Vale a dire, se si intende attraversare un confine e quindi si intende attraversarlo nuovamente, il valore indicato dalle due intenzioni prese insieme è il valore indicato da nessuno di essi.

Vale a dire, per qualsiasi confine, riattraversare non è attraversare.

T H E F O R M

We take as given the idea of distinction and the idea of indication, and that we cannot make an indication without drawing a distinction. We take, therefore, the form of distinction for the form.

Definition

Distinction is perfect continence.

That is to say, a distinction is drawn by arranging a boundary with separate sides so that a point on one side cannot reach the other side without crossing the boundary. For example,in a plane space a circle draws a distinction.

Once a distinction is drawn, the spaces, states, or contents on each side of the boundary, being distinct, can be indicated.

There can be no distinction without motive, and there can be no motive unless contents are seen to differ in value.

If a content is of value, a name can be taken to indicate this value.

Thus the calling of the name can be identified with the value of the content.

Axiom 1. The law of calling

The value of a call made again is the value of the call.

That is to say, if a name is called and then is called again, the value indicated by the two calls taken together is the value indicated by one of them.

That is to say, for any name, to recall is to call.

That is to say, for any name, to recall is to call.

Equally, if the content is of value, a motive or an intention or instruction to cross the boundary into the content can be taken to indicate this value.

Thus, also, the crossing of the boundary can be identified with the value of the content.

Axiom 2 . The law of crossing

The value of a crossing made again is not the value of the crossing.

That is to say, if it is intended to cross a boundary and then it is intended to cross it again, the value indicated by the twointentions taken together is the value indicated by none of them.

That is to say, if it is intended to cross a boundary and then it is intended to cross it again, the value indicated by the twointentions taken together is the value indicated by none of them.

That is to say, for any boundary, to recross is not to cross.

Nel seguito definisce come le forme vengano estratte dalle forme:

F O R M E E S T R A T T E D A L L E F O R M E

Costruzione

Tracciate una distinzione.

Contenuto

Chiamatela la prima distinzione.

Chiamate lo spazio in cui è operata lo spazio tagliato o ferito dalla distinzione.

Chiamare le parti dello spazio modellate dalla rottura o tagliate ai lati della distinzione o, in alternativa, gli spazi, stati o contenuti distinti per mezzo della distinzione.

Intento

Lasciate che qualsiasi segno, simbolo, o firma essere preso in ogni modo con o in relazione alla distinzione come un segnale.

Chiamate l'uso di qualsiasi segnale il suo intento.

Primo canone. Convenzione dell'intenzione

Sia l'intento di un segnale limitato all'uso consentito ad esso.

Chiamate questo la convenzione di intenzione. In generale, ciò che non è permesso è proibito.

Conoscenza

Sia uno stato caratterizzato dalla distinzione essere contrassegnato con un marchio

di distinzione.

Sia lo stato riconosciuto dal marchio.

Chiamate lo stato lo stato marcato.

Forma

Chiamate lo spazio spaccata da qualsiasi distinzione, insieme con l'intero contenuto dello spazio, la forma della distinzione.

Chiamate la forma della prima distinzione la forma.

Nome

Sia una forma distinta dalla forma.

Sia il segno di distinzione copiato dalla forma su un'altra forma.

Chiamate qualsiasi di tali copie del marchio un segno del marchio.

Lasciate che ogni segno del marchio sia chiamato come il nome dello stato marcato.

Lasciate che il nome indicano lo stato.

Disposizione

Chiamate la forma di un numero di token considerata per quanto riguarda l'uno all'altro (cioè, considerato nella stessa forma) una disposizione.

Espressione

Chiamate ogni disposizione intese come un indicatore un'espressione.

Valore

Chiamate uno stato indicato da un'espressione il valore dell'espressione.

Sia lo stato riconosciuto dal marchio.

Chiamate lo stato lo stato marcato.

Forma

Chiamate lo spazio spaccata da qualsiasi distinzione, insieme con l'intero contenuto dello spazio, la forma della distinzione.

Chiamate la forma della prima distinzione la forma.

Nome

Sia una forma distinta dalla forma.

Sia il segno di distinzione copiato dalla forma su un'altra forma.

Chiamate qualsiasi di tali copie del marchio un segno del marchio.

Lasciate che ogni segno del marchio sia chiamato come il nome dello stato marcato.

Lasciate che il nome indicano lo stato.

Disposizione

Chiamate la forma di un numero di token considerata per quanto riguarda l'uno all'altro (cioè, considerato nella stessa forma) una disposizione.

Espressione

Chiamate ogni disposizione intese come un indicatore un'espressione.

Valore

Chiamate uno stato indicato da un'espressione il valore dell'espressione.

F O R M S T A K E N O U T O F T H E F O RM

Construction

Draw a distinction.

Draw a distinction.

Content

Call it the first distinction.

Call the space in which it is drawn the space severed or cloven by the distinction.

Call the parts of the space shaped by the severance or cleft the sides of the distinction or, alternatively, the spaces, states,or contents distinguished by the distinction.

Intent

Let any mark, token, or sign be taken in any way with or with regard to the distinction as a signal.

Call the use of any signal its intent.

First canon. Convention of intention

Let the intent of a signal be limited to the use allowed to it.

Call this the convention of intention. In general, what is not allowed is forbidden.

Let the intent of a signal be limited to the use allowed to it.

Call this the convention of intention. In general, what is not allowed is forbidden.

Knowledge

Let a state distinguished by the distinction be marked with a mark

Let a state distinguished by the distinction be marked with a mark

of distinction.

Let the state be known by the mark.

Call the state the marked state.

Form

Call the space cloven by any distinction, together with the entire content of the space, the form of the distinction.

Call the form of the first distinction the form.

Name

Let there be a form distinct from the form.

Let the mark of distinction be copied out of the form into such another form.

Call any such copy of the mark a token of the mark.

Let any token of the mark be called as a name of the marked state.

Let the name indicate the state.

Arrangement

Call the form of a number of tokens considered with regard to one another (that is to say, considered in the same form) an arrangement.

Expression

Call any arrangement intended as an indicator an expression.

Value

Call a state indicated by an expression the value of the expression.

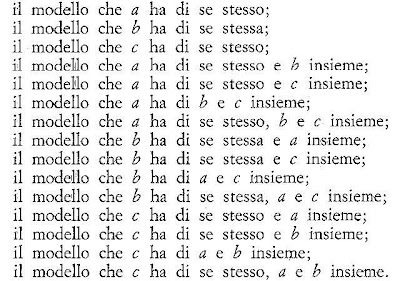

L'operatore di segno (mark o cross):

è il simbolo principale utilizzato da Brown.

Il simbolo rappresenta la distinzione tra il suo interno e l'esterno:

Lo stato interno definito dal simbolo è detto stato segnato, quello esterno stato non-segnato, intendendo per stato i due lati di una distinzione, e il simbolo stesso rappresenta la distinzione tra i due stati: