La ricerca del Sé e della Coscienza nella prospettiva enazionista, considerando mondi di coscienza ed esperienza senza fondamento analizzato secondo la tradizione del Buddhismo Abhidharma, implica diverse considerazioni etiche, tra le quali la principale è la compassione (con - passione) che nella tradizione Buddhista è, insieme alla saggezza (prajñā), una delle due basi di fondamento:

WORLDS WITHOUT GROUND

Laying Down a Path in Walking

Ethics and Human Transformation

Compassion: Worlds without Ground

If planetary thinking requires that we embody the realization of groundlessness in a scientific culture, planetary building requires the embodiment of concern for the other with whom we enact a world. The tradition of mindfulness/awareness offers a path by which this may actually be brought about.

The mindfulness/awareness student first begins to see in a precise fashion what the mind is doing, its restless, perpetual grasping, moment to moment. This enables the student to cut some of the automaticity of his habitual patterns, which leads to further mindfulness, and he begins to realize that there is no self in any of his actual experience. This can be disturbing and offers the temptation to swing to the other extreme, producing moments of loss of heart. The philosophical flight into nihilism that we saw earlier in this chapter mirrors a psychological process: the reflex to grasp is so strong and deep seated that we reify the absence of a solid foundation into a solid absence or abyss.

As the student goes on, however, and his mind relaxes further into awareness, a sense of warmth and inclusiveness dawns. The street fighter mentality of watchful self-interest can be let go somewhat to be replaced by interest in others. We are already other-directed even at our most negative, and we already feel warmth toward some people, such as family and friends. The conscious realization of the sense of relatedness and the development of a more impartial sense of warmth are encouraged in the mindfulness/awareness tradition by various contemplative practices such as the generation of loving-kindness. It is said that the full realization of groundlessness (sunyata) cannot occur if there is no warmth.

For this reason, in the Mahayana tradition, which we have so far presented as being centrally concerned with groundlessness as sunyata, there is an equally central and complementary concern with groundlessness as compassion.ll In fact, most of the traditional Mahayana presentations do not begin with groundlessness but rather with the cultivation of compassion for all sentient beings. Nagarjuna, for example, states in one of his works that the Mahayana teaching has "an essence of emptiness and compassion." This statement is sometimes paraphrased by saying that emptiness (sunyata) is full of compassion (karuna).

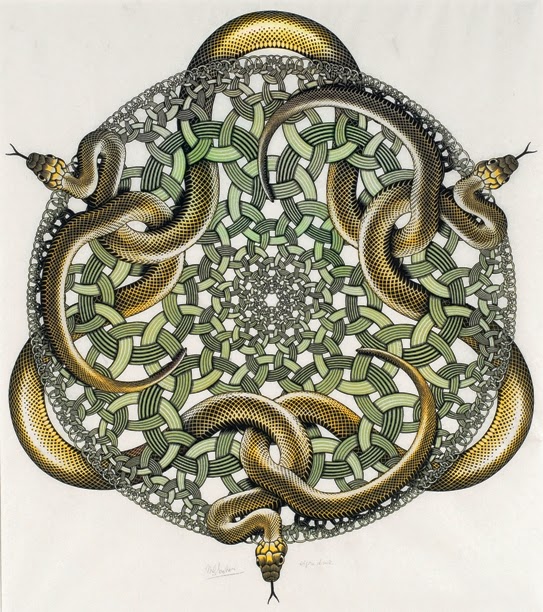

Thus sunyata, the loss of a fixed reference point or ground in either self, other, or a relationship between them, is said to be inseparable from compassion like the two sides of a coin or the two wings of a bird. Our natural impulse, in this view, is one of compassion, but it has been obscured by habits of ego-clinging like the sun obscured by a passing cloud.

This is by no means the end of the path, however. For some traditions, there is a further step to be made in understanding beyond the sunyata of codependent origination-that is, the sunyata of naturalness. Up to now, we have been talking about the contents of realization in primarily negative terms: no-self, egolessness, no world, nonduality, emptiness, groundlessness. In actual fact, the majority of the world's Buddhists do not speak of their deepest concerns in negative terms; these negatives are preliminaries-necessary to remove habitual patterns of grasping, unsurpassably important and precious, but nonetheless preliminaries-that are pointing toward the realization of a positively conceived state. The Western world-for example, Christianity-although pleased to engage in dialogue with the negating aspects of Buddhism (perhaps as a way of speaking to the nihilism in our own tradition), steadfastly (at times even self-consciously) tends to ignore the Buddhist positive.

To be sure, the Buddhist positive is threatening. It is no ground whatsoever; it cannot be grasped as ground, reference point, or nest for a sense of ego. It does not exist-nor does it not exist. It cannot be an object of mind or of the conceptualizing process; it cannot be seen, heard, or thought-thus the many traditional images for it: the sight of a blind man, a flower blooming in the sky. When the conceptual mind tries to grasp it, it finds nothing, and so it experiences it as emptiness. It can be known (and can only be known) directly. It is called Buddha nature, no mind, primordial mind, absolute bodhicitta, wisdom mind, warrior's mind, all goodness, great perfection, that which cannot be fabricated by mind, naturalness. It is not a hair's breadth different from the ordinary world; it is that very same ordinary, conditional, impermanent, painful, groundless world experienced (known) as the unconditional, supreme state. And the natural manifestation, the embodiment, of this state is compassion-unconditional, fearless, ruthless, spontaneous compassion.

What do we mean by unconditional compassion? We need to backtrack and consider the development of compassion from the more mundane point of view of the student. The possibility for compassionate concern for others, which is present in all humans, is usually mixed with the sense of ego and so becomes confused with the need to satisfy one's own cravings for recognition and self-evaluation. The spontaneous compassion that arises when one is not caught in the habitual patterns-when one is not performing volitional actions out of karmic cause and effect-is not done with a sense of need for feedback from its recipient. It is the anxiety about feedback-the response of the other-that causes us tension and inhibition in our action. When action is done without the business-deal mentality, there can be relaxation. This is called supreme (or transcendental) generosity.

If this seems abstract, the reader might try a brief exercise. We usually read books like this with some heavy-handed sense of purpose. Imagine for a moment that you are reading this solely in order to benefit others. Does that change the feeling tone of the task?

When discussing wisdom from the point of view of compassion, the Sanskrit term often used is bodhicitta, which has been variously translated as "enlightened mind," "the heart of the enlightened state of mind," or simply "awakened heart." Bodhicitta is said to have two aspects, one absolute and one relative. Absolute bodhicitta is the term applied to whatever state is considered ultimate or fundamental in a given Buddhist tradition-the experience of the groundlessness of sunyata or the (positively defined) sudden glimpse of the natural, awake state itself. Relative bodhicitta is that fundamental warmth toward the phenomenal world that practitioners report arises from absolute experience and that manifests itself as concern for the welfare of others beyond merely naive compassion. As opposed to the order in which we have previously described these experiences, it is said that the development of a sense of unproblematical warmth toward the world leads to the experience of the flash of absolute bodhicitta.

Buddhist practitioners obviously do not realize any of these things (even mindfulness) all at once. They report that they catch glimpses that encourage them to make further efforts. One of the most important steps consists in developing compassion toward one's own grasping fixation on ego-self. The idea behind this attitude is that confronting one's own grasping tendencies is a friendly act toward oneself. As this friendliness develops, one's awareness and concern for those around one enlarges as well. It is at this point that one can begin to envision a more open-ended and nonegocentric compassion.

Another characteristic of the spontaneous compassion that does not arise out of the volitional action of habitual patterns is that it follows no rules. It is not derived from an axiomatic ethical system nor even from pragmatic moral injunctions. It is completely responsive to the needs of the particular situation. Nagarjuna conveys this attitude of responsiveness:

Unrealized practioners, of course, cannot dispense with rules and moral injunctions. There are many ethical rules in Buddhism whose aim is to put the body and mind into a form that imitates as nearly as possible how genuine compassion might become manifest in that situation (just as the meditative sitting posture is said to be an imitation of enlightenment).

With respect to its situational specificity and its responsiveness, this view of nonegocentric compassion might seem similar to what has been discussed in certain recent psychoanalytic writings as "ethical know-how." In the case of compassionate concern as generated in the context of mindfulness/awareness, this know-how could be said to be based in responsiveness to oneself and others as sentient beings without ego-selves who suffer because they grasp after ego-selves. And this attitude of responsiveness is in tum rooted in an ongoing concern: How can groundlessness be revealed ethically as nonegocentric compassion?

Compassionate action is also called skillful means (upaya) in Buddhism. Skillful means are inseparable from wisdom. It is interesting to consider the relationship of skillful means to ordinary skills such as learning to drive a car or learning to play the violin. Is ethical action (compassionate action) in Buddhism to be considered a skill-perhaps analogous to the Heidegger/Dreyfus account of ethical action as a non-rule-based, developed skill? As we discussed at some length with respect to meditation practice, in some ways skillful means in Buddhism could be seen as similar to our notion of a skill: the student practices ("plants good seeds")-that is, avoids harmful actions, performs beneficial ones, meditates. Unlike an ordinary skill, however, in skillful means the ultimate effect of these practices is to remove all egocentric habits so that the practitioner can realize the wisdom state, and compassionate action can arise directly and spontaneously out of wisdom. It is as if one were born already knowing how to play the violin and had to practice with great exertion only to remove the habits that prevented one from displaying that virtuosity.

It should by now be obvious that the ethics of compassion has nothing to do with satisfying some pleasure principle. From the standpoint of mindfulness/awareness, it is fundamentally impossible to satisfy desires that are born within the grasping mind. A sense of unconditional well-being arises only through letting go of the grasping mind. There is, however, no reason for ascetism. Material and social goods are to be employed however the situation warrants. (The middle way between the extremes of ascetism and indulgence is actually the historically earIiest sense in which the term middle way was employed in Buddhism.)

The results of the path of mindful, open-ended learning are profoundly transformative. Instead of being embodied (more accurately, reembodied moment after moment) out of struggle, habit, and sense of self, the goal is to become embodied out of compassion for the world. The Tibetan tradition even talks about the five aggregates being transformed into the five wisdoms. Notice that this sense of transformation does not mean going away from the world-getting out of the five aggregates. The aggregates may be the constituents on which the inaccurate sense of self and world are based, but (more properly and) they are also the basis of wisdom. The means of transforming the aggregates into wisdom is knowledge, realizing the aggregates accurately-empty of any egoistic ground whatsoever yet filled with unconditional goodness (Buddha nature, etc.), intrinsically just as they are in themselves.

How can such an attitude of all encompassing, decentered, responsive, compassionate concern be fostered and embodied in our culture? It obviously cannot be created merely through norms and rationalistic injunctions. It must be developed and embodied through a discipline that facilitates letting go of ego-centered habits and enables compassion to become spontaneous and self-sustaining. The point is not that there is no need for normative rules in the relative world---clearly such rules are a necessity in any society. It is that unless such rules are informed by the wisdom that enables them to be dissolved in the demands of responsivity to the particularity and immediacy of lived situations, the rules will become sterile, scholastic hindrances to compassionate action rather than conduits for its manifestation.

Perhaps less obvious but even more strongly enjoined by the mindfulness/awareness tradition is that meditations and practices undertaken simply as self-improvement schemes will foster only egohood. Because of the strength of egocentric habitual conditioning, there is a constant tendency, as practitioners in all contemplative traditions are aware, to try to grasp, possess, and become proud of the slightest insight, glimpse of openness, or understanding. Unless such tendencies become part of the path of letting go that leads to compassion, then insights can actually do more harm than good. Buddhist teachers have often written that it is far better to remain as an ordinary person and believe in ultimate foundations than to cling to some remembered experience of groundlessnes without manifesting compassion.

Finally, talk alone will certainly not suffice to engender spontaneous nonegocentric concern. Even more than experiences of insight, words and concepts can be easily grasped at, taken as ground, and woven into a cloak of egohood. Teachers in all contemplative traditions warn against fixated views and concepts taken as reality. Indeed, our promulgations of the concept of enactive cognitive science give us some pause. We would surely not want to trade the relative humility of objectivism for the hubris of thinking that we construct our world. Better by far a straightforward cognitivist than a bloated and solipsistic enactivist.

We simply cannot overlook the need for some form of sustained, disciplined practice. This is not something that one can make up for oneself-any more than one can make up the history of Western science for oneself. Nothing will take its place; one cannot just do one form of science rather than another and think that one is gaining wisdom or becoming ethical. Individuals must personally discover and admit their own sense of ego in order to go beyond it. Although this happens at the individual level, it has implications for science and for society.

Compassion: Worlds without Ground

If planetary thinking requires that we embody the realization of groundlessness in a scientific culture, planetary building requires the embodiment of concern for the other with whom we enact a world. The tradition of mindfulness/awareness offers a path by which this may actually be brought about.

The mindfulness/awareness student first begins to see in a precise fashion what the mind is doing, its restless, perpetual grasping, moment to moment. This enables the student to cut some of the automaticity of his habitual patterns, which leads to further mindfulness, and he begins to realize that there is no self in any of his actual experience. This can be disturbing and offers the temptation to swing to the other extreme, producing moments of loss of heart. The philosophical flight into nihilism that we saw earlier in this chapter mirrors a psychological process: the reflex to grasp is so strong and deep seated that we reify the absence of a solid foundation into a solid absence or abyss.

As the student goes on, however, and his mind relaxes further into awareness, a sense of warmth and inclusiveness dawns. The street fighter mentality of watchful self-interest can be let go somewhat to be replaced by interest in others. We are already other-directed even at our most negative, and we already feel warmth toward some people, such as family and friends. The conscious realization of the sense of relatedness and the development of a more impartial sense of warmth are encouraged in the mindfulness/awareness tradition by various contemplative practices such as the generation of loving-kindness. It is said that the full realization of groundlessness (sunyata) cannot occur if there is no warmth.

For this reason, in the Mahayana tradition, which we have so far presented as being centrally concerned with groundlessness as sunyata, there is an equally central and complementary concern with groundlessness as compassion.ll In fact, most of the traditional Mahayana presentations do not begin with groundlessness but rather with the cultivation of compassion for all sentient beings. Nagarjuna, for example, states in one of his works that the Mahayana teaching has "an essence of emptiness and compassion." This statement is sometimes paraphrased by saying that emptiness (sunyata) is full of compassion (karuna).

Thus sunyata, the loss of a fixed reference point or ground in either self, other, or a relationship between them, is said to be inseparable from compassion like the two sides of a coin or the two wings of a bird. Our natural impulse, in this view, is one of compassion, but it has been obscured by habits of ego-clinging like the sun obscured by a passing cloud.

This is by no means the end of the path, however. For some traditions, there is a further step to be made in understanding beyond the sunyata of codependent origination-that is, the sunyata of naturalness. Up to now, we have been talking about the contents of realization in primarily negative terms: no-self, egolessness, no world, nonduality, emptiness, groundlessness. In actual fact, the majority of the world's Buddhists do not speak of their deepest concerns in negative terms; these negatives are preliminaries-necessary to remove habitual patterns of grasping, unsurpassably important and precious, but nonetheless preliminaries-that are pointing toward the realization of a positively conceived state. The Western world-for example, Christianity-although pleased to engage in dialogue with the negating aspects of Buddhism (perhaps as a way of speaking to the nihilism in our own tradition), steadfastly (at times even self-consciously) tends to ignore the Buddhist positive.

To be sure, the Buddhist positive is threatening. It is no ground whatsoever; it cannot be grasped as ground, reference point, or nest for a sense of ego. It does not exist-nor does it not exist. It cannot be an object of mind or of the conceptualizing process; it cannot be seen, heard, or thought-thus the many traditional images for it: the sight of a blind man, a flower blooming in the sky. When the conceptual mind tries to grasp it, it finds nothing, and so it experiences it as emptiness. It can be known (and can only be known) directly. It is called Buddha nature, no mind, primordial mind, absolute bodhicitta, wisdom mind, warrior's mind, all goodness, great perfection, that which cannot be fabricated by mind, naturalness. It is not a hair's breadth different from the ordinary world; it is that very same ordinary, conditional, impermanent, painful, groundless world experienced (known) as the unconditional, supreme state. And the natural manifestation, the embodiment, of this state is compassion-unconditional, fearless, ruthless, spontaneous compassion.

"When the reasoning mind no longer clings and grasps, ... one awakens into the wisdom with which one was born, and compassionate energy arises without pretense."

|

| Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche |

If this seems abstract, the reader might try a brief exercise. We usually read books like this with some heavy-handed sense of purpose. Imagine for a moment that you are reading this solely in order to benefit others. Does that change the feeling tone of the task?

When discussing wisdom from the point of view of compassion, the Sanskrit term often used is bodhicitta, which has been variously translated as "enlightened mind," "the heart of the enlightened state of mind," or simply "awakened heart." Bodhicitta is said to have two aspects, one absolute and one relative. Absolute bodhicitta is the term applied to whatever state is considered ultimate or fundamental in a given Buddhist tradition-the experience of the groundlessness of sunyata or the (positively defined) sudden glimpse of the natural, awake state itself. Relative bodhicitta is that fundamental warmth toward the phenomenal world that practitioners report arises from absolute experience and that manifests itself as concern for the welfare of others beyond merely naive compassion. As opposed to the order in which we have previously described these experiences, it is said that the development of a sense of unproblematical warmth toward the world leads to the experience of the flash of absolute bodhicitta.

Buddhist practitioners obviously do not realize any of these things (even mindfulness) all at once. They report that they catch glimpses that encourage them to make further efforts. One of the most important steps consists in developing compassion toward one's own grasping fixation on ego-self. The idea behind this attitude is that confronting one's own grasping tendencies is a friendly act toward oneself. As this friendliness develops, one's awareness and concern for those around one enlarges as well. It is at this point that one can begin to envision a more open-ended and nonegocentric compassion.

Another characteristic of the spontaneous compassion that does not arise out of the volitional action of habitual patterns is that it follows no rules. It is not derived from an axiomatic ethical system nor even from pragmatic moral injunctions. It is completely responsive to the needs of the particular situation. Nagarjuna conveys this attitude of responsiveness:

Just as the grammarian makes one study grammar,

A Buddha teaches according to the tolerance of his students;

Some he urges to refrain from sins, others to do good,

Some to rely on dualism, others on non-dualism;

And to some he teaches the profound,

The terrifying, the practice of enlightenment,

Whose essence is emptiness that is compassion.

With respect to its situational specificity and its responsiveness, this view of nonegocentric compassion might seem similar to what has been discussed in certain recent psychoanalytic writings as "ethical know-how." In the case of compassionate concern as generated in the context of mindfulness/awareness, this know-how could be said to be based in responsiveness to oneself and others as sentient beings without ego-selves who suffer because they grasp after ego-selves. And this attitude of responsiveness is in tum rooted in an ongoing concern: How can groundlessness be revealed ethically as nonegocentric compassion?

Compassionate action is also called skillful means (upaya) in Buddhism. Skillful means are inseparable from wisdom. It is interesting to consider the relationship of skillful means to ordinary skills such as learning to drive a car or learning to play the violin. Is ethical action (compassionate action) in Buddhism to be considered a skill-perhaps analogous to the Heidegger/Dreyfus account of ethical action as a non-rule-based, developed skill? As we discussed at some length with respect to meditation practice, in some ways skillful means in Buddhism could be seen as similar to our notion of a skill: the student practices ("plants good seeds")-that is, avoids harmful actions, performs beneficial ones, meditates. Unlike an ordinary skill, however, in skillful means the ultimate effect of these practices is to remove all egocentric habits so that the practitioner can realize the wisdom state, and compassionate action can arise directly and spontaneously out of wisdom. It is as if one were born already knowing how to play the violin and had to practice with great exertion only to remove the habits that prevented one from displaying that virtuosity.

It should by now be obvious that the ethics of compassion has nothing to do with satisfying some pleasure principle. From the standpoint of mindfulness/awareness, it is fundamentally impossible to satisfy desires that are born within the grasping mind. A sense of unconditional well-being arises only through letting go of the grasping mind. There is, however, no reason for ascetism. Material and social goods are to be employed however the situation warrants. (The middle way between the extremes of ascetism and indulgence is actually the historically earIiest sense in which the term middle way was employed in Buddhism.)

The results of the path of mindful, open-ended learning are profoundly transformative. Instead of being embodied (more accurately, reembodied moment after moment) out of struggle, habit, and sense of self, the goal is to become embodied out of compassion for the world. The Tibetan tradition even talks about the five aggregates being transformed into the five wisdoms. Notice that this sense of transformation does not mean going away from the world-getting out of the five aggregates. The aggregates may be the constituents on which the inaccurate sense of self and world are based, but (more properly and) they are also the basis of wisdom. The means of transforming the aggregates into wisdom is knowledge, realizing the aggregates accurately-empty of any egoistic ground whatsoever yet filled with unconditional goodness (Buddha nature, etc.), intrinsically just as they are in themselves.

How can such an attitude of all encompassing, decentered, responsive, compassionate concern be fostered and embodied in our culture? It obviously cannot be created merely through norms and rationalistic injunctions. It must be developed and embodied through a discipline that facilitates letting go of ego-centered habits and enables compassion to become spontaneous and self-sustaining. The point is not that there is no need for normative rules in the relative world---clearly such rules are a necessity in any society. It is that unless such rules are informed by the wisdom that enables them to be dissolved in the demands of responsivity to the particularity and immediacy of lived situations, the rules will become sterile, scholastic hindrances to compassionate action rather than conduits for its manifestation.

Perhaps less obvious but even more strongly enjoined by the mindfulness/awareness tradition is that meditations and practices undertaken simply as self-improvement schemes will foster only egohood. Because of the strength of egocentric habitual conditioning, there is a constant tendency, as practitioners in all contemplative traditions are aware, to try to grasp, possess, and become proud of the slightest insight, glimpse of openness, or understanding. Unless such tendencies become part of the path of letting go that leads to compassion, then insights can actually do more harm than good. Buddhist teachers have often written that it is far better to remain as an ordinary person and believe in ultimate foundations than to cling to some remembered experience of groundlessnes without manifesting compassion.

Finally, talk alone will certainly not suffice to engender spontaneous nonegocentric concern. Even more than experiences of insight, words and concepts can be easily grasped at, taken as ground, and woven into a cloak of egohood. Teachers in all contemplative traditions warn against fixated views and concepts taken as reality. Indeed, our promulgations of the concept of enactive cognitive science give us some pause. We would surely not want to trade the relative humility of objectivism for the hubris of thinking that we construct our world. Better by far a straightforward cognitivist than a bloated and solipsistic enactivist.

We simply cannot overlook the need for some form of sustained, disciplined practice. This is not something that one can make up for oneself-any more than one can make up the history of Western science for oneself. Nothing will take its place; one cannot just do one form of science rather than another and think that one is gaining wisdom or becoming ethical. Individuals must personally discover and admit their own sense of ego in order to go beyond it. Although this happens at the individual level, it has implications for science and for society.