|

| Alexander Nevsky Monastery, Saint Petersburg, Saint Petersburg Federal City, Russian Federation |

venerdì 4 aprile 2014

giovedì 3 aprile 2014

approccio sistemico al Tao

|

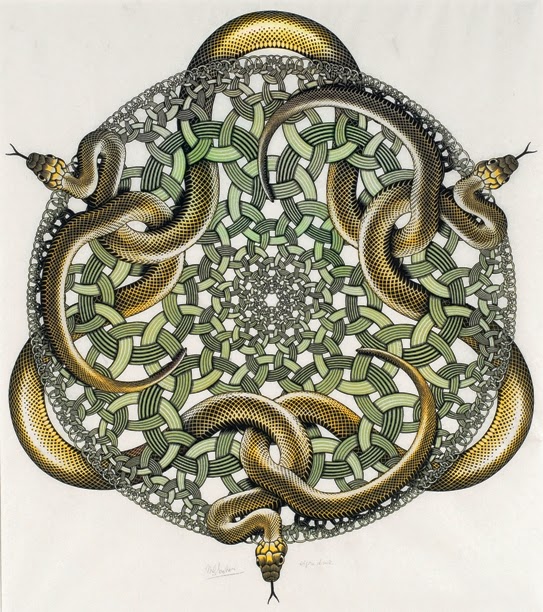

| M.C. Escher, Snakes, 1969, woodcut in orange, green and black, printed from 3 blocks |

Charles T. Tart riassume in questo capitolo le varie strategie per la descrizione sistemica della coscienza:

Strategies in Using the Systems Approach

The systems approach generates a number of strategies for studying states of consciousness. Some of these are unique consequences of using a system approach, some are just good-sense strategies that could come from other approaches. Many of these methodological strategies have been touched on in previous chapters; some are brought out in later chapters. Here I bring together most of these methodological points and introduce some new ones.

The Constructed Nature of Consciousness

Realizing that the ordinary d-SoC is not natural and given, but constructed according to semiarbitrary cultural constraints, gives us the freedom to ask some basic questions that might not otherwise occur to us. And it should make us more cautious about labeling other states as "pathological" and other cultures as "primitive." The Australian bushmen, for example, are almost universally considered one of the world's most primitive cultures because of their nomadic life and their paucity of material possessions.

Yet Pearce argues that, from another point of view, these people are among the most sophisticated in the world, for they have organized their entire culture around achieving a certain d-ASC, which they refer to as the experience of "Dream Time." Our bias toward material possessions, however, makes us unable to see this. Recognizing the semiarbitrary nature of the system of the ordinary d-SoC that has been constructed in our culture should make us especially aware of the implicit assumptions built into it, assumptions were so taken for granted that it never occurs to us to question them. In Transpersonal Psychologies, nine expert practitioners of various spiritual disciplines wrote about their disciplines not as religions, but as psychologies. In the course of editing these contributions, I was increasingly struck by the way certain assumptions are made in various spiritual psychologies that are different from or contrary to those made in Western psychology. As a result, I wrote a chapter outlining several dozen assumptions that have become implicit for Western psychologies and that, by virtue of being implicit, have great control over us. I have found that when asked what some of these assumptions are, I have great difficulty recalling them: I have to go back and look at what I wrote! Although my study of systems that make different assumptions brought these implicit assumptions to mind, they have already sunk back to the implicit assumptions to mind, they have already sunk back to the implicit level. We should not underestimate the power of culturally given assumptions in controlling us, and we cannot overestimate the importance of trying to come to grips with them. We should also recognize that the enculturation process, discussed earlier, ties the reward and punishment subsystems to the maintenance and defense of ordinary consensus reality. We are afraid of experiencing d-ASCs that are foreign to us and this fear strengthens our tendency to classify them as abnormal or pathological and to avoid them. It also further strengthens our resolve to deal with all reality from the point of view of the ordinary d-SoC, using only the tool or coping function of the ordinary d-SoC. But since the ordinary d-SoC is a limited tool, good for some things but not for others, we invariable distort parts of reality. The tendency to ignore or fight what we do not consider valuable and to distort our perceptions to make them fit is good for maintaining a cohesive social system, but poor for promoting scientific inquiry. A possible solution is the proposal for establishing state-specific sciences.

The Importance of Awareness

The systems approach stresses the importance of attention/awareness as an activating energy within any d-SoC. Yet if we ask what awareness is or how we direct it and so call it attention, we cannot supply satisfactory answers. We may deal with this problem simply by taking basic awareness for granted, as we are forced to do at this level of development of the systems approach, and work with it even though we do not know what it is. After all, we do not really know what gravity is in any ultimate sense, but we can measure what it does and from that information develop, for example, a science of ballistics. We can learn much about d-SoCs in the systems approach if we just take basic awareness and attention/awareness energy for granted, but we must eventually focus on questions about the nature of awareness. We will have to consider the conservative and radical views of the mind to determine whether awareness is simply the product of brain and nervous system functioning or whether it is something more.

System Qualities

The systems approach emphasizes that even though a d-SoC is made up of components, the overall system has gestalt qualities that cannot be predicted from knowledge of the components alone. Thus, while investigation of the components, the subsystems and structures, is important, such investigative emphasis must be balanced by studies of the overall system's functioning. We must become familiar with the pattern of the overall system's functioning so we can avoid wasting energy on researching components that turn out to be relatively unimportant in the overall system. We might, for example, avoid spending excessive research effort and money, as is now being done, on investigating physiological effects of marijuana intoxication, as we have seen, indicates that psychological factors are at least as important as the drug factor in determining the nature of the d-ASC produced. The systems approach also emphasizes the need to examine the system's functioning under the conditions in which it was designed to function. We are not yet sure what, if anything, d-ASCs are particularly designed for, what particular they have. We must find this out. On the other hand, we should try not to waste effort studying d-ASCs under conditions they were clearly not designed for.

For example, conducting studies that show a slight decrement in arithmetical skills under marijuana intoxication is of some interest, but since no record exists of anyone using marijuana in order to solve arithmetical problems, such studies are somewhat irrelevant. This emphasizes a point made earlier: that it is generally useless to characterize any d-ASC as "better" or "worse" than any other d-SoC. The question should always be, "Better or worse for what particular task?" All d-ASCs we know of seem to associated with improved functioning for certain kinds of tasks and worsened functioning for others. An important research aim, then, is to find out what d-ASCs are optimal for particular tasks and how to train people to enter efficiently into that d-ASC when they need to perform that task. This runs counter to a strong, implicit assumption in our culture that the ordinary d-SoC is the best one for all tasks; that assumption is highly questionable when it is made explicit. Remember that in any d-SoC there is a limited selection from the full range of human potential. While some of these latent human potentials may be developable in the ordinary d-SoC, some are more available in a d-ASC. Insofar as we consider some of these potentials valuable, we must learn what d-SoCs they are operable in and how to train them for good functioning within those d-SoCs.

This last point is not an academic issue: enormous numbers of people are now personally experimenting with d-ASCs to attain some of these potentials. While much gain will undoubtedly come out of this personal experimentation, we should also expect much loss.

Individual Differences

As we have seen, what for one individual is a d-ASC may, for another individual, be merely part of the region of his ordinary d-SoC, one continuous experiential space. By following the common experimental procedure of using group data rather than data from individual subjects, we can get the impression of continuity (one d-SoC) when two or more d-SoCs actually occurred within the experimental procedure. We should indeed search for general laws of the mind that hold across individuals, but we must beware of enunciating such laws prematurely without first understanding the behavior and experiences of the individuals within our experiments.

Recognizing the importance of individual differences has many application outside the laboratory. If a friend tries some spiritual technique and has a marvelous experience as a result, and you try the same technique with no result, there is not necessarily something wrong with you. Rather, because of differences in the structures of your ordinary d-SoCs, that particular technique mobilizes attention/awareness energy in an effective way to produce a certain experience for him, but is not an effective techniques for you.

Operationalism, Relevant and Irrelevant

Operationalism is a way of rigorously defining some concept by describing the actual operations required to produce it. Thus an operational definition of the concept of "nailing" is defined by the operations (1) pick up a hammer in your right hand; (2) pick up a nail in your left hand; (3) put the point of the nail on a wood surface and hold the nail perpendicular to the wood surface; (4) strike the head of the nail with the hammer and then lift the hammer again; and (5) repeat step 4 until the head of the nail is flush with the surface of the wood. An operational definition is a precise definition, allowing total reproducibility.

Some claim that whatever cannot be defined operationally is not a legitimate subject for scientific investigation. That is silly. No one can precisely specify all the steps necessary to experience "being in love," but that is hardly justification for ignoring the state of being in love as an important human situation worthy of study. A further problem is that in psychology, operationalism implicitly means physical operationalism, specifying the overt, physically observable steps in a process in order to define it. In the search for an objectivity like that of the physical sciences, psychologists emphasize aspects of their discipline that can be physically measured, but often at the cost of irrelevant studies.

An example is the equating of the hypnotic state, the d-ASC of hypnosis, with the performance of the hypnotic induction procedure. The hypnotic state is a psychological construct or, if induction has been successful, an experiential reality to the hypnotized person. It is not defined by external measurements. There are no obvious behavioral manifestations that clearly indicate hypnosis has occurred and no known physiological changes that invariably accompany hypnosis. The hypnotic procedure, on the other had, the words that they hypnotist says aloud, is highly amenable to physical measurement. An investigator can film the hypnotic procedure, tape-record the hypnotist's voice, measure the sound intensity of the hypnotist's voice, and accumulate a variety of precise, reproducible physical measurements. But that investigator makes a serious mistake if he then describes the responses of the "hypnotized subject" and means by "hypnotized subject" the person to whom the hypnotist said the words. The fact that the hypnotist performs the procedure does not guarantee that the subject enters the d-ASC of hypnosis. As discussed earlier, a person's b-SoC is multiply stabilized, and no single induction procedure or combination of induction procedures will, with certainty, destabilize the ordinary state and produce a particular d-ASC.

I stress that the concept of the d-SoC is a psychological, experiential construct. Thus, the ultimate criterion for determining whether a person is in a d-ASC is a map of his experiences that shows him to be in a region of psychological space we have termed a d-ASC. The external performance of an induction technique is not the same as achievement of the desired d-ASC. A hypnotic induction procedure does not necessarily induce hypnosis; lying down in bed does not necessarily induce sleeping or dreaming; performing a meditation exercise does not necessarily induce a meditative state.

When an induction procedure is physiological, as when a drug is used, the temptation to equate the induction procedure with the altered state is especially great. But the two are not the same, even in this case. As discussed in Chapter 10, smoking marijuana does not necessarily cause a transition out of the b-SoC. Nor is knowledge of the dose of the drug an adequate specification of depth.

We do need to describe techniques in detail in our reports of d-ASCs, but we must also specify the degree to which these techniques were actually effective in altering a subject's state of consciousness, and we must specify this for each individual subject. In practice, physiological criteria may be sometimes so highly correlated with experiential reports indicating a d-ASC that those criteria can be considered an indicator that the d-ASC has occurred. This is the case with stage 1 REM dreaming. Behavioral criteria may be similarly correlated with experiential data, though I am not sure any such criteria are well correlated at present. But the primary criteria are well correlated at present. But the primary criterion is an actual assessment of the kind of experiential space the subject is in that indicates the induction procedure was effective. Operationalism, then, which uses external, physical, and behavioral criteria, is inadequate for dealing with many of the most important phenomena of d-ASCs. Most of the phenomena that define d-ASCs are internal and may never show obvious behavioral or physiological[2] manifestations. Ultimately we need an experiential operationalism, a set of statements such as (1) if you stop all evaluation processes for at least three minutes, (2) and you concurrently invest no attention/awareness energy into the Interoception subsystem for perceiving the body, (3) so that all perception of the body fades out, then (4) you will experience a mental phenomenon of such and such a type. Our present language is not well suited to this, as discussed earlier, so we are a long way from a good experiential operationalism. The level of precision of understanding and communication that an experiential operationalism will bring is very high; nevertheless, we should not overvalue operationalism and abandon hope of understanding a phenomenon we cannot define operationally.

Predictive Capabilities of the Systems Approach

In Chapter 8 I briefly describe some basic subsystems we can recognize in terms of current knowledge. We can now see how the systems approach can be used to make testable predictions about d-SoCs.

The basic predictive operation is cyclical. The first step is to observe the properties of structures/subsystems as well as you can from the current state of knowledge. You ask questions in terms of what you already know. Then you take the second step of organizing the observations to make better theoretical models of the structures/subsystems you have observed. The third step is to predict, on the basis of the models, how the structures/subsystems can and cannot interact with each other under various conditions. Fourth, you test these predictions by looking for or attempting to create d-SoCs that fit or do not fit these improved structure/subsystem models and seeing how well the models work. This takes you back to the first step, starting the cycle again, further altering or refining your models, etc.

The systems approach providers a conceptual framework for organizing knowledge about states of consciousness and a process for continually improving knowledge about the structures/subsystems. The ten subsystems sketched in Chapter 8 are crude concepts at this stage of our knowledge and should eventually be replaced with more precise concepts about the exact nature of a larger number of more basic subsystems and about their possibilities for interaction to form systems.

I have given little thought so far to making predictions based on the present state of the systems approach. The far more urgent need at this current, chaotic stage of the new science of consciousness is to organize the mass of unrelated data we have into manageable form. I believe that most of the data now available can be usefully organized in the systems approach and that to do so will be a clear step forward. The precise fitting of the available mass of data into this approach will, however, take years of work.

One obvious prediction of the systems theory is that because the differing properties of structures restrict their interaction, there is a definite limit to the number of stable d-SoCs. Ignoring enculturation, we can say that the number is large but limited by the biological/neurological/psychical endowment of man in general, by humanness. The number of possible states for a particular individual is even smaller because enculturation further limits the qualities of structures.

My systems approach to consciousness appears to differ from Lilly's approach to consciousness as a human biocomputer. I predict that only certain configurations can occur and constitute stable states of consciousness, d-SoCs. Lilly's model seems to treat the mind as a general-purpose computer, capable of being programmed in any way one can conceive of: "In the province of the mind, what one believes to true either is true or becomes true within certain limits." Personal conversations between Lilly and I suggest that our positions actually do not differ that much. The phrase "within certain limits" is important here. I agree entirely with Lilly's belief that what we currently believe to be the limits, the "basic" structures limiting the mind are probably mostly arbitrary, programmed structures peculiar to our culture and personal history. It is the discovery of the really basic structures behind these arbitrary cultural/personal ones that will tell us about the basic nature of the human mind. The earlier discussion of individual differences is highly relevant here, for it can applied across cultures: two regions of experiential space that are d-SoCs for many or all individuals in a particular culture may be simply parts of one large region of experiential space for many or all individuals in another culture.

I stress again, however, that our need today, and the primary value of the systems approach, is useful organization of data and guidance in asking questions, not prediction. Prediction and hypothesis-testing will come into their own in a few years as our understanding of structures/subsystems sharpens.

Stability and Growth

Implicit in the act of mapping an individual's psychological experiences is the assumption of a reasonable degree of stability of the individual's structure and functioning over time. The work necessary to obtain a map would be wasted if the map had to be changed before it had been used. Ordinarily we assume that an individual's personality or ordinary d-SoC is reasonably stable over quite long periods, generally over a lifetime once his basic personality has been formed by late adolescence. Exceptions to this assumption occur when individuals are exposed to severe, abnormal conditions, such as disasters, which may radically alter parts of their personality structure, or to psychotherapy and related psychological growth techniques. Although the personality change following psychotherapy is often rather small, leaving the former map of the individual's personality relatively useful, it is sometimes quite large.

The validity of assuming this kind of stability in relation to research on d-SoCs is questionable. The people who are most interested in experiencing d-ASCs are dissatisfied with the ordinary d-SoC and so may be actively trying to change it. But studies confined to people not very interested in d-ASCs (so-called naive subjects) may be dealing with an unusual group who are afraid of d-ASCs. Stability of the b-SoC or of repeatedly induced d-ASCs is something to be assessed, not assumed. This is particularly true for a person's early experiences with a d-ASC, where he is learning how to function in the d-ASC with each new occurrence. In my study of the experiences of marijuana intoxication. I deliberately excluded users who had had less than a dozen experiences of being stoned on marijuana. The experience of these naive users would have mainly reflect learning to cope with a new state, rather than the common, stable characteristics of the d-ASC of being stoned.

An individual may eventually learn to merge two d-SoCs into one. The merger may be a matter of transferring some state-specific experiences and potentials back into the ordinary state, so that eventually most or many state-specific experiences are available in the ordinary state. The ordinary state, in turn, undergoes certain changes in its configuration. Or, growth or therapeutic work at the extremes of functioning of two d-SoCs may gradually bring the two closer until experiences are possible all through the former "forbidden region."

Pseudomerging of two d-SoCs may also be possible. As an individual more and more frequently makes the transitions between the two states, he may automate the transition process to the point where he no longer has any awareness of it, and/or efficient routes through the transition process are so thoroughly learned that the transition takes almost no tie or effort. Then, unless the individual or an observer was examining his whole pattern of functioning, his state of consciousness might appear to be single simply because transitions were not noticed. This latter case would be like the rapid, automated transitions between identity states within the ordinary state of consciousness. Since a greater number of human potentials are available in two states than in one, such merging or learning of rapid transitions can be seen as growth. Whether the individual or his culture sees it as growth depends on cultural valuations of the added potentials and the individual's own intelligence in actual utilization of the two states. The availability of more potentials does not guarantee their wise or adaptive use.

Sequential Strategies in Studying d-SoCs

The sequential strategies for investigating d-SoCs that follow from the systems approach are outlined below. These strategies are idealistic and subject to modification in practice.

First, the general experiential, behavioral or physiological components of a rough concept of a particular d-ASC are mapped. The data may come from informal interviews with a number of people who have experienced that state, from personal experiences in that d-ASC. This exercise supplies a feeling for the overall territory and its main features.

Then the experiential space of various individuals is mapped to determine whether their experiences show the distinctive clusterings and patternings that constitute d-SoCs. This step overlaps somewhat with the first, for the investigator assumes or has data to indicate a distinctness about the d-ASC for at least some individuals as a start of his interest.

For individuals who show this discreteness, the third step of more detailed individual investigation is carried out. For those who do not, studies are begun across individuals to ascertain why some show various discrete states and others do not: in addition to recognizing the existence of individual differences, the researcher must find out why they exist and what function they serve.

The third step is to map the various d-SoCs of particular individuals in detail. What are the main features of each state? What induction procedures produce the state? What deinduction procedures cause a person to transit out of it? What are the limits of stability of the state? What uses, advantages does the state have? What disadvantages or dangers? How is the depth measured? What are the convenient marker phenomena to rapidly measure depth?

With this background, the investigator can profitable ask questions about interindividual similarities of the various discrete states. Are they really enough alike across individuals to warrant a common state name? If so, does this relate mainly to cultural background similarities of the individuals studied or to some more fundamental aspect of the nature of the human mind? Finally, even more detailed studies can be done on the nature of particular discrete states and the structures/subsystems comprising them. This sort of investigation should come at a late stage to avoid premature reductionism: we must not repeat psychology's early mistake of trying to find the universal Laws of the Mind before we have good empirical maps of the territory.

The Constructed Nature of Consciousness

Realizing that the ordinary d-SoC is not natural and given, but constructed according to semiarbitrary cultural constraints, gives us the freedom to ask some basic questions that might not otherwise occur to us. And it should make us more cautious about labeling other states as "pathological" and other cultures as "primitive." The Australian bushmen, for example, are almost universally considered one of the world's most primitive cultures because of their nomadic life and their paucity of material possessions.

Yet Pearce argues that, from another point of view, these people are among the most sophisticated in the world, for they have organized their entire culture around achieving a certain d-ASC, which they refer to as the experience of "Dream Time." Our bias toward material possessions, however, makes us unable to see this. Recognizing the semiarbitrary nature of the system of the ordinary d-SoC that has been constructed in our culture should make us especially aware of the implicit assumptions built into it, assumptions were so taken for granted that it never occurs to us to question them. In Transpersonal Psychologies, nine expert practitioners of various spiritual disciplines wrote about their disciplines not as religions, but as psychologies. In the course of editing these contributions, I was increasingly struck by the way certain assumptions are made in various spiritual psychologies that are different from or contrary to those made in Western psychology. As a result, I wrote a chapter outlining several dozen assumptions that have become implicit for Western psychologies and that, by virtue of being implicit, have great control over us. I have found that when asked what some of these assumptions are, I have great difficulty recalling them: I have to go back and look at what I wrote! Although my study of systems that make different assumptions brought these implicit assumptions to mind, they have already sunk back to the implicit assumptions to mind, they have already sunk back to the implicit level. We should not underestimate the power of culturally given assumptions in controlling us, and we cannot overestimate the importance of trying to come to grips with them. We should also recognize that the enculturation process, discussed earlier, ties the reward and punishment subsystems to the maintenance and defense of ordinary consensus reality. We are afraid of experiencing d-ASCs that are foreign to us and this fear strengthens our tendency to classify them as abnormal or pathological and to avoid them. It also further strengthens our resolve to deal with all reality from the point of view of the ordinary d-SoC, using only the tool or coping function of the ordinary d-SoC. But since the ordinary d-SoC is a limited tool, good for some things but not for others, we invariable distort parts of reality. The tendency to ignore or fight what we do not consider valuable and to distort our perceptions to make them fit is good for maintaining a cohesive social system, but poor for promoting scientific inquiry. A possible solution is the proposal for establishing state-specific sciences.

The Importance of Awareness

The systems approach stresses the importance of attention/awareness as an activating energy within any d-SoC. Yet if we ask what awareness is or how we direct it and so call it attention, we cannot supply satisfactory answers. We may deal with this problem simply by taking basic awareness for granted, as we are forced to do at this level of development of the systems approach, and work with it even though we do not know what it is. After all, we do not really know what gravity is in any ultimate sense, but we can measure what it does and from that information develop, for example, a science of ballistics. We can learn much about d-SoCs in the systems approach if we just take basic awareness and attention/awareness energy for granted, but we must eventually focus on questions about the nature of awareness. We will have to consider the conservative and radical views of the mind to determine whether awareness is simply the product of brain and nervous system functioning or whether it is something more.

System Qualities

The systems approach emphasizes that even though a d-SoC is made up of components, the overall system has gestalt qualities that cannot be predicted from knowledge of the components alone. Thus, while investigation of the components, the subsystems and structures, is important, such investigative emphasis must be balanced by studies of the overall system's functioning. We must become familiar with the pattern of the overall system's functioning so we can avoid wasting energy on researching components that turn out to be relatively unimportant in the overall system. We might, for example, avoid spending excessive research effort and money, as is now being done, on investigating physiological effects of marijuana intoxication, as we have seen, indicates that psychological factors are at least as important as the drug factor in determining the nature of the d-ASC produced. The systems approach also emphasizes the need to examine the system's functioning under the conditions in which it was designed to function. We are not yet sure what, if anything, d-ASCs are particularly designed for, what particular they have. We must find this out. On the other hand, we should try not to waste effort studying d-ASCs under conditions they were clearly not designed for.

For example, conducting studies that show a slight decrement in arithmetical skills under marijuana intoxication is of some interest, but since no record exists of anyone using marijuana in order to solve arithmetical problems, such studies are somewhat irrelevant. This emphasizes a point made earlier: that it is generally useless to characterize any d-ASC as "better" or "worse" than any other d-SoC. The question should always be, "Better or worse for what particular task?" All d-ASCs we know of seem to associated with improved functioning for certain kinds of tasks and worsened functioning for others. An important research aim, then, is to find out what d-ASCs are optimal for particular tasks and how to train people to enter efficiently into that d-ASC when they need to perform that task. This runs counter to a strong, implicit assumption in our culture that the ordinary d-SoC is the best one for all tasks; that assumption is highly questionable when it is made explicit. Remember that in any d-SoC there is a limited selection from the full range of human potential. While some of these latent human potentials may be developable in the ordinary d-SoC, some are more available in a d-ASC. Insofar as we consider some of these potentials valuable, we must learn what d-SoCs they are operable in and how to train them for good functioning within those d-SoCs.

This last point is not an academic issue: enormous numbers of people are now personally experimenting with d-ASCs to attain some of these potentials. While much gain will undoubtedly come out of this personal experimentation, we should also expect much loss.

Individual Differences

As we have seen, what for one individual is a d-ASC may, for another individual, be merely part of the region of his ordinary d-SoC, one continuous experiential space. By following the common experimental procedure of using group data rather than data from individual subjects, we can get the impression of continuity (one d-SoC) when two or more d-SoCs actually occurred within the experimental procedure. We should indeed search for general laws of the mind that hold across individuals, but we must beware of enunciating such laws prematurely without first understanding the behavior and experiences of the individuals within our experiments.

Recognizing the importance of individual differences has many application outside the laboratory. If a friend tries some spiritual technique and has a marvelous experience as a result, and you try the same technique with no result, there is not necessarily something wrong with you. Rather, because of differences in the structures of your ordinary d-SoCs, that particular technique mobilizes attention/awareness energy in an effective way to produce a certain experience for him, but is not an effective techniques for you.

Operationalism, Relevant and Irrelevant

Operationalism is a way of rigorously defining some concept by describing the actual operations required to produce it. Thus an operational definition of the concept of "nailing" is defined by the operations (1) pick up a hammer in your right hand; (2) pick up a nail in your left hand; (3) put the point of the nail on a wood surface and hold the nail perpendicular to the wood surface; (4) strike the head of the nail with the hammer and then lift the hammer again; and (5) repeat step 4 until the head of the nail is flush with the surface of the wood. An operational definition is a precise definition, allowing total reproducibility.

Some claim that whatever cannot be defined operationally is not a legitimate subject for scientific investigation. That is silly. No one can precisely specify all the steps necessary to experience "being in love," but that is hardly justification for ignoring the state of being in love as an important human situation worthy of study. A further problem is that in psychology, operationalism implicitly means physical operationalism, specifying the overt, physically observable steps in a process in order to define it. In the search for an objectivity like that of the physical sciences, psychologists emphasize aspects of their discipline that can be physically measured, but often at the cost of irrelevant studies.

An example is the equating of the hypnotic state, the d-ASC of hypnosis, with the performance of the hypnotic induction procedure. The hypnotic state is a psychological construct or, if induction has been successful, an experiential reality to the hypnotized person. It is not defined by external measurements. There are no obvious behavioral manifestations that clearly indicate hypnosis has occurred and no known physiological changes that invariably accompany hypnosis. The hypnotic procedure, on the other had, the words that they hypnotist says aloud, is highly amenable to physical measurement. An investigator can film the hypnotic procedure, tape-record the hypnotist's voice, measure the sound intensity of the hypnotist's voice, and accumulate a variety of precise, reproducible physical measurements. But that investigator makes a serious mistake if he then describes the responses of the "hypnotized subject" and means by "hypnotized subject" the person to whom the hypnotist said the words. The fact that the hypnotist performs the procedure does not guarantee that the subject enters the d-ASC of hypnosis. As discussed earlier, a person's b-SoC is multiply stabilized, and no single induction procedure or combination of induction procedures will, with certainty, destabilize the ordinary state and produce a particular d-ASC.

I stress that the concept of the d-SoC is a psychological, experiential construct. Thus, the ultimate criterion for determining whether a person is in a d-ASC is a map of his experiences that shows him to be in a region of psychological space we have termed a d-ASC. The external performance of an induction technique is not the same as achievement of the desired d-ASC. A hypnotic induction procedure does not necessarily induce hypnosis; lying down in bed does not necessarily induce sleeping or dreaming; performing a meditation exercise does not necessarily induce a meditative state.

When an induction procedure is physiological, as when a drug is used, the temptation to equate the induction procedure with the altered state is especially great. But the two are not the same, even in this case. As discussed in Chapter 10, smoking marijuana does not necessarily cause a transition out of the b-SoC. Nor is knowledge of the dose of the drug an adequate specification of depth.

We do need to describe techniques in detail in our reports of d-ASCs, but we must also specify the degree to which these techniques were actually effective in altering a subject's state of consciousness, and we must specify this for each individual subject. In practice, physiological criteria may be sometimes so highly correlated with experiential reports indicating a d-ASC that those criteria can be considered an indicator that the d-ASC has occurred. This is the case with stage 1 REM dreaming. Behavioral criteria may be similarly correlated with experiential data, though I am not sure any such criteria are well correlated at present. But the primary criteria are well correlated at present. But the primary criterion is an actual assessment of the kind of experiential space the subject is in that indicates the induction procedure was effective. Operationalism, then, which uses external, physical, and behavioral criteria, is inadequate for dealing with many of the most important phenomena of d-ASCs. Most of the phenomena that define d-ASCs are internal and may never show obvious behavioral or physiological[2] manifestations. Ultimately we need an experiential operationalism, a set of statements such as (1) if you stop all evaluation processes for at least three minutes, (2) and you concurrently invest no attention/awareness energy into the Interoception subsystem for perceiving the body, (3) so that all perception of the body fades out, then (4) you will experience a mental phenomenon of such and such a type. Our present language is not well suited to this, as discussed earlier, so we are a long way from a good experiential operationalism. The level of precision of understanding and communication that an experiential operationalism will bring is very high; nevertheless, we should not overvalue operationalism and abandon hope of understanding a phenomenon we cannot define operationally.

Predictive Capabilities of the Systems Approach

In Chapter 8 I briefly describe some basic subsystems we can recognize in terms of current knowledge. We can now see how the systems approach can be used to make testable predictions about d-SoCs.

The basic predictive operation is cyclical. The first step is to observe the properties of structures/subsystems as well as you can from the current state of knowledge. You ask questions in terms of what you already know. Then you take the second step of organizing the observations to make better theoretical models of the structures/subsystems you have observed. The third step is to predict, on the basis of the models, how the structures/subsystems can and cannot interact with each other under various conditions. Fourth, you test these predictions by looking for or attempting to create d-SoCs that fit or do not fit these improved structure/subsystem models and seeing how well the models work. This takes you back to the first step, starting the cycle again, further altering or refining your models, etc.

The systems approach providers a conceptual framework for organizing knowledge about states of consciousness and a process for continually improving knowledge about the structures/subsystems. The ten subsystems sketched in Chapter 8 are crude concepts at this stage of our knowledge and should eventually be replaced with more precise concepts about the exact nature of a larger number of more basic subsystems and about their possibilities for interaction to form systems.

I have given little thought so far to making predictions based on the present state of the systems approach. The far more urgent need at this current, chaotic stage of the new science of consciousness is to organize the mass of unrelated data we have into manageable form. I believe that most of the data now available can be usefully organized in the systems approach and that to do so will be a clear step forward. The precise fitting of the available mass of data into this approach will, however, take years of work.

One obvious prediction of the systems theory is that because the differing properties of structures restrict their interaction, there is a definite limit to the number of stable d-SoCs. Ignoring enculturation, we can say that the number is large but limited by the biological/neurological/psychical endowment of man in general, by humanness. The number of possible states for a particular individual is even smaller because enculturation further limits the qualities of structures.

My systems approach to consciousness appears to differ from Lilly's approach to consciousness as a human biocomputer. I predict that only certain configurations can occur and constitute stable states of consciousness, d-SoCs. Lilly's model seems to treat the mind as a general-purpose computer, capable of being programmed in any way one can conceive of: "In the province of the mind, what one believes to true either is true or becomes true within certain limits." Personal conversations between Lilly and I suggest that our positions actually do not differ that much. The phrase "within certain limits" is important here. I agree entirely with Lilly's belief that what we currently believe to be the limits, the "basic" structures limiting the mind are probably mostly arbitrary, programmed structures peculiar to our culture and personal history. It is the discovery of the really basic structures behind these arbitrary cultural/personal ones that will tell us about the basic nature of the human mind. The earlier discussion of individual differences is highly relevant here, for it can applied across cultures: two regions of experiential space that are d-SoCs for many or all individuals in a particular culture may be simply parts of one large region of experiential space for many or all individuals in another culture.

I stress again, however, that our need today, and the primary value of the systems approach, is useful organization of data and guidance in asking questions, not prediction. Prediction and hypothesis-testing will come into their own in a few years as our understanding of structures/subsystems sharpens.

Stability and Growth

Implicit in the act of mapping an individual's psychological experiences is the assumption of a reasonable degree of stability of the individual's structure and functioning over time. The work necessary to obtain a map would be wasted if the map had to be changed before it had been used. Ordinarily we assume that an individual's personality or ordinary d-SoC is reasonably stable over quite long periods, generally over a lifetime once his basic personality has been formed by late adolescence. Exceptions to this assumption occur when individuals are exposed to severe, abnormal conditions, such as disasters, which may radically alter parts of their personality structure, or to psychotherapy and related psychological growth techniques. Although the personality change following psychotherapy is often rather small, leaving the former map of the individual's personality relatively useful, it is sometimes quite large.

The validity of assuming this kind of stability in relation to research on d-SoCs is questionable. The people who are most interested in experiencing d-ASCs are dissatisfied with the ordinary d-SoC and so may be actively trying to change it. But studies confined to people not very interested in d-ASCs (so-called naive subjects) may be dealing with an unusual group who are afraid of d-ASCs. Stability of the b-SoC or of repeatedly induced d-ASCs is something to be assessed, not assumed. This is particularly true for a person's early experiences with a d-ASC, where he is learning how to function in the d-ASC with each new occurrence. In my study of the experiences of marijuana intoxication. I deliberately excluded users who had had less than a dozen experiences of being stoned on marijuana. The experience of these naive users would have mainly reflect learning to cope with a new state, rather than the common, stable characteristics of the d-ASC of being stoned.

An individual may eventually learn to merge two d-SoCs into one. The merger may be a matter of transferring some state-specific experiences and potentials back into the ordinary state, so that eventually most or many state-specific experiences are available in the ordinary state. The ordinary state, in turn, undergoes certain changes in its configuration. Or, growth or therapeutic work at the extremes of functioning of two d-SoCs may gradually bring the two closer until experiences are possible all through the former "forbidden region."

Pseudomerging of two d-SoCs may also be possible. As an individual more and more frequently makes the transitions between the two states, he may automate the transition process to the point where he no longer has any awareness of it, and/or efficient routes through the transition process are so thoroughly learned that the transition takes almost no tie or effort. Then, unless the individual or an observer was examining his whole pattern of functioning, his state of consciousness might appear to be single simply because transitions were not noticed. This latter case would be like the rapid, automated transitions between identity states within the ordinary state of consciousness. Since a greater number of human potentials are available in two states than in one, such merging or learning of rapid transitions can be seen as growth. Whether the individual or his culture sees it as growth depends on cultural valuations of the added potentials and the individual's own intelligence in actual utilization of the two states. The availability of more potentials does not guarantee their wise or adaptive use.

Sequential Strategies in Studying d-SoCs

The sequential strategies for investigating d-SoCs that follow from the systems approach are outlined below. These strategies are idealistic and subject to modification in practice.

First, the general experiential, behavioral or physiological components of a rough concept of a particular d-ASC are mapped. The data may come from informal interviews with a number of people who have experienced that state, from personal experiences in that d-ASC. This exercise supplies a feeling for the overall territory and its main features.

Then the experiential space of various individuals is mapped to determine whether their experiences show the distinctive clusterings and patternings that constitute d-SoCs. This step overlaps somewhat with the first, for the investigator assumes or has data to indicate a distinctness about the d-ASC for at least some individuals as a start of his interest.

For individuals who show this discreteness, the third step of more detailed individual investigation is carried out. For those who do not, studies are begun across individuals to ascertain why some show various discrete states and others do not: in addition to recognizing the existence of individual differences, the researcher must find out why they exist and what function they serve.

The third step is to map the various d-SoCs of particular individuals in detail. What are the main features of each state? What induction procedures produce the state? What deinduction procedures cause a person to transit out of it? What are the limits of stability of the state? What uses, advantages does the state have? What disadvantages or dangers? How is the depth measured? What are the convenient marker phenomena to rapidly measure depth?

With this background, the investigator can profitable ask questions about interindividual similarities of the various discrete states. Are they really enough alike across individuals to warrant a common state name? If so, does this relate mainly to cultural background similarities of the individuals studied or to some more fundamental aspect of the nature of the human mind? Finally, even more detailed studies can be done on the nature of particular discrete states and the structures/subsystems comprising them. This sort of investigation should come at a late stage to avoid premature reductionism: we must not repeat psychology's early mistake of trying to find the universal Laws of the Mind before we have good empirical maps of the territory.

Etichette:

GDPs,

Tao Livello 3 e oltre

mercoledì 2 aprile 2014

realizzazione del Tao

La realizzazione del Sé è un bisogno fondamentale?

Innanzitutto cerca di capire cosa si intende per realizzazione del Sé. E’ stato A.H. Maslow a usare questo termine. L’uomo è nato come potenzialità: non è un’attualità, è solo potenziale.

L’uomo è nato come possibilità, non come attualità. Può diventare qualcosa. Può realizzare come non realizzare le sue potenzialità. Può sfruttare come non sfruttare l’opportunità e la natura non ti costringe a realizzarti. Sei libero. Puoi scegliere di realizzarti come di non fare nulla al riguardo. L’uomo nasce come seme. Quindi, nessuno è nato già realizzato, ma solo con la possibilità della realizzazione. Se le cose stanno così – e le cose stanno così – la realizzazione del Sé diventa un bisogno fondamentale, perché se non sei realizzato, se non diventi ciò che puoi essere o ciò che sei destinato a essere, se il tuo destino non si compie, se non ti realizzi, se il tuo seme non diventa un albero realizzato, sentirai che ti manca qualcosa. E tutti lo sentono. Questo senso di mancanza in realtà è dovuto al fatto che non ti sei ancora realizzato. In realtà non è che a mancarti sono le ricchezze o una posizione, il prestigio o il potere. Anche se ti venisse dato tutto ciò che chiedi – ricchezze, potere, prestigio, qualunque cosa – avresti questa impressione costante che manchi qualcosa dentro di te, perché questo “qualcosa che manca” non ha alcun rapporto con ciò che è esterno: riguarda la tua crescita interiore. Percepirai questo senso di mancanza a meno che non ti realizzi, se non giungi a una realizzazione, a una fioritura, a un appagamento interiore nel quale senti di essere ciò che dovevi essere. E non potrai distruggere questa sensazione con nessun’altra cosa. Perciò realizzazione del Sé significa che una persona è diventata quello che doveva essere: era nata come seme e ora è fiorita. E’ giunta al suo completo sviluppo, uno sviluppo interiore, è giunta al termine interiore. Non appena senti che tutte le tue potenzialità si sono attuate, sentirai anche l’apice della vita, dell’amore, dell’esistenza stessa. Abraham Maslow, ha anche coniato un altro termine: “Esperienza della vetta”.

Quando una persona realizza se stessa, raggiunge un culmine, una vetta di beatitudine. Allora non c’è più smania di nulla: è totalmente appagata da se stessa. Ora non le manca più nulla: non c’è più desiderio, richiesta, movimento. Qualsiasi cosa sia, è totalmente appagata da se stessa. La realizzazione del Sé diventa un’esperienza culminante, e solo un individuo realizzato può vivere esperienze culminanti. Allora qualsiasi cosa tocchi, qualsiasi cosa faccia o non faccia – anche il semplice esistere – per lui è un’esperienza culminante, il semplice esistere è beatitudine.

Perciò la beatitudine non riguarda nulla di esterno, è solamente una conseguenza della crescita interiore. Un Buddha è un individuo che ha realizzato se stesso: questa è la ragione per la quale raffiguriamo il Buddha, Mahavira e altri – in sculture, in pitture e in qualsiasi raffigurazione – che siedono su un loto pienamente sbocciato.

Questo loto pienamente sbocciato è il culmine della fioritura interiore. Nell’interiorità sono fioriti e sbocciati pienamente. Questa fioritura interiore produce una radiosità, una rugiada di beatitudine che emana costantemente da loro. Basta andare sotto la loro ombra, avvicinarsi a loro, per sentirsi avvolti dal silenzio. C’è un interessante aneddoto su Mahavira. E’ un mito, ma i miti sono affascinanti e possono esprimere molte cose che non potrebbero essere dette in altro modo. Si narra che quando Mahavira si spostava, tutt’intorno a lui, per un raggio di circa quaranta chilometri, tutti i fiori sbocciassero, anche se non era stagione. Questa è solo un’immagine poetica, ma persino una persona che non ha realizzato il Sé, se venisse in contatto con Mahavira, sarebbe contagiata dalla sua fioritura e sentirebbe anche in se stessa una fioritura interiore. Anche se non fosse la stagione giusta per quella persona, anche se non fosse pronta, la rifletterebbe, sentirebbe un’eco. Se Mahavira fosse vicino a qualcuno, quella persona sentirebbe un’eco dentro di sé, e avrebbe una visione fugace di ciò che potrebbe essere. La realizzazione del Sé è il bisogno fondamentale, e quando dico fondamentale, intendo che ti sentiresti incompiuto anche se tutti i tuoi bisogni venissero soddisfatti, tutti accetto questo. Se, al contrario, accadesse la realizzazione del Sé senza che si compisse nient’altro, sentiresti comunque un profondo, totale compimento. Questa è la ragione per la quale il Buddha era un mendicante, eppure un imperatore. Quando s’illuminò, il Buddha andò a Kashi. Il re andò a fargli visita e gli chiese: “Vedo che tu non hai nulla. Sei solo un mendicante, eppure io mi sento un mendicante in confronto a te. Non hai nulla, ma il modo in cui cammini, in cui guardi, in cui ridi, fa sembrare che l’intero mondo sia il tuo regno, e tu non possiedi nulla di visibile, nulla di nulla. Dov’è quindi il segreto del tuo potere? Sembri un imperatore”. In realtà nessun imperatore ha mai avuto un aspetto così regale – come se tutto il mondo gli appartenesse. “Tu sei il re, ma dov’è il tuo potere, la fonte?” E il Buddha disse: “E’ in me. Il mio potere, la fonte del mio potere, tutto quello che senti intorno a me, in realtà è dentro di me. Non ho nulla salvo me stesso, ma questo è sufficiente. Sono realizzato; ora non desidero più nulla. Sono diventato privo di desideri”. In realtà, un individuo che abbia realizzato se stesso diventerà privo di desideri. Ricordati di questo: in genere diciamo che, se diventi privo di desideri, conoscerai te stesso. Ma è più esatto il contrario: se conosci te stesso diventerai privo di desideri. E l’accento del Tantra non è sull’essere senza desideri, ma sull’avere realizzato se stessi. Da questo consegue l’assenza di desideri. Desiderio significa che non sei realizzato interiormente. Ti manca qualcosa, perciò la desideri e continui a saltare da un desiderio all’altro in cerca dell’appagamento. Questa ricerca è infinita, perché un desiderio ne crea un altro. In realtà, un desiderio ne crea dieci. Se ricerchi uno stato di beatitudine senza desideri attraverso dei desideri, non arriverai da nessuna parte. Ma se provi qualcos’altro – metodi per la realizzazione del Sé, per realizzare la tua potenzialità interiore, per attuarla – quanto più ti realizzerai tanto meno desidererai, perché, in realtà, desideri perché sei interiormente vuoto. Quando non sei più vuoto nell’interiorità, smetti di desiderare.

Che cosa si deve fare per realizzare il Sé? Ci sono due cose da capire.

La prima: realizzazione del Sé non significa che, se diventi un grande pittore, un grande musicista o un grande poeta avrai realizzato te stesso. E’ ovvio che una parte di te sarà realizzata, e anche questo dà una grande soddisfazione. Se hai il talento per diventare un buon musicista, e se lo metti a frutto e diventi musicista, una parte di te sarà compiuta – ma non la totalità. L’umanità che rimane dentro di te resterà incompiuta. Sarai in uno squilibrio: una parte sarà cresciuta e il resto sarà rimasto come una pietra appesa al tuo collo. Guarda un poeta. Quando è in vena poetica sembra un Buddha: dimentica se stesso completamente. E’ come se nel poeta l’uomo comune non ci fosse più. Perciò quando un poeta è in vena, ha una vetta – una vetta parziale. E a volte i poeti hanno visioni fugaci che accadono solo a menti illuminate, come quella del Buddha. Un poeta può parlare come un Buddha. Per esempio Kahlil Gibran: parla come un Buddha, ma non è un Buddha. E’ un poeta, un grande poeta. Perciò, se vedi Kahlil Gibran attraverso la sua poesia, assomiglia al Buddha, a Cristo o Krishna, ma se vai dall’uomo Kahlil Gibran, scoprirai che è una persona comunissima. Parla dell’amore in un modo talmente meraviglioso che, forse, neppure un Buddha potrebbe farlo. Ma un Buddha conosce l’amore con l’intero suo essere. Kahlil Gibran conosce l’amore quando è trasportato dalla poesia. Quando vola, sulla ali della poesia ha delle visioni fugaci dell’amore, intuizioni meravigliose, e le ha espresse con rara penetrazione. Ma se vai a vedere il vero Kahlil Gibran, l’uomo, sentirai una sproporzione. Il poeta e l’uomo sono separati, remoti l’uno dall’altro. Il poeta sembra essere qualcosa che talvolta capita a quest’uomo, ma quest’uomo non è il poeta. Questa è la ragione per la quale i poeti sentono che, quando stanno creando della poesia, è qualcun altro che la sta creando, non sono loro. Si sentono come se fossero diventati veicoli di qualche altra energia, di qualche altra forza. Loro non ci sono più. In realtà hanno questa sensazione perché si è realizzata solo una parte, un frammento di loro, non la totalità. Non hai toccato il cielo: solo un dito ha toccato il cielo, e tu rimani radicato in terra. A volte salti, e per un istante non sei più sulla terra; ti sei beffato della gravità. Ma il momento successivo sei di nuovo per terra. Se un poeta si sente realizzato, avrà delle visioni fugaci – delle visioni fugaci e parziali. Se un musicista si sente realizzato, avrà delle visioni fugaci. Si dice che quando Beethoven era sul palcoscenico, sul podio, era un uomo differente, completamente diverso. Goethe ha detto quando Beethoven era sul podio a dirigere la sua orchestra sembrava un dio. Non si poteva dire che era un uomo comune. Non era affatto un uomo: era sovrumano. Il modo in cui guardava, il modo in cui alzava le mani, era tutto sovrumano. Ma quando scendeva dal podio, era solo un uomo comune, L’uomo sul podio sembrava posseduto da qualcos’altro, come se Beethoven non ci fosse più e qualche altra forza fosse entrata in lui. Sceso dal podio era di nuovo Beethoven, l’uomo. E’ per questo che i poeti, i musicisti, i grandi artisti, la gente creativa sono più tesi: perché hanno due tipi di essere. L’uomo comune non è così teso perché vive sempre in un solo: vive sulla terra; mentre i poeti, i musicisti, i grandi artisti saltano, vanno al di là della gravità. In certi momenti non sono più su questa Terra, non fanno più parte dell’umanità. Diventano parte del mondo dei Buddha – il paese dei Buddha. Poi tornano di nuovo qui. Hanno due punti di esistenza; le loro personalità sono scisse. Perciò ogni artista creativo, ogni grande artista è in un certo senso squilibrato. La tensione è immensa! La frattura, L’intervallo tra questi due tipi di esistenza è grandissimo – insormontabilmente grande! A volte l’artista è solo un uomo comune, a volte diventa simile a un Buddha. E’ diviso tra questi due punti, ma ha delle visioni fugaci. Quando parlo di realizzazione del Sé, non intendo che devi diventare un grande poeta o un grande musicista. Intendo che devi diventare un uomo totale. Non dico un grande uomo perché un grande uomo è sempre parziale. La grandezza in qualcosa è sempre parziale. Una persona continua incessantemente a muoversi in una direzione sola, e rimane la stessa in tutte le altre, è sbilanciata. Quando dico di diventare un uomo totale non intendo che tu diventi un grande uomo, ti dico: “Crea un equilibrio, sii centrato, sii realizzato come uomo – non come musicista, non come poeta, non come artista, sii realizzato come uomo”. Che cosa significa essere compiuti come uomini? Un grande poeta è tale grazie alla sua grande poesia. Un grande musicista è tale grazie alla sua grande musica. Un grande uomo è tale per certe cose che ha fatto: potrebbe essere un grande eroe. Un grande uomo è parziale in ogni direzione. La grandezza è parziale, frammentaria. Ecco perché i grandi uomini devono affrontare un’angoscia maggiore rispetto alle persone comuni. Che cos’è l’uomo totale? Che cosa si intende con essere un uomo intero, un uomo totale? Innanzitutto significa essere centrati, non esistere senza un centro. In questo istante sei qualcosa e l’istante successivo sei qualcos’altro. Le persone vengono da me e in genere chiedo loro: “Dov’è che sentite il vostro centro – nel cuore, nella mente, nell’ombelico – dove? Nel centro sessuale? Dove? Dov’è che sentite il vostro centro?”. Di solito rispondono: “A volte lo sento nella testa, altre nel cuore, altre ancora non lo sento affatto”. Quindi dico loro di chiudere gli occhi di fronte a me e di percepirlo proprio in quell’istante. Nella maggioranza dei casi succede che dicano: “Proprio ora, per un attimo, sento di essere centrato nella testa”. Ma l’istante dopo non sono più lì. Dicono: ”Sono nel cuore”. E un momento dopo il centro è già fuggito via, è altrove, nel centro sessuale o da qualche altra parte. In realtà non sei centrato, lo sei solo momentaneamente. Ogni istante ha il suo centro, perciò tu continui a muoverti. Quando la mente funziona, senti che il centro è la testa; Quando sei innamorato, senti che lo è il cuore; quando non stai facendo nulla di particolare, sei confuso: non riesci a trovare dove sia il centro, poiché riesci a farlo solo mentre stai lavorando, mentre stai facendo qualcosa. In quel caso una particolare parte del tuo corpo diventa il centro. Ma tu non sei centrato. Se non fai nulla non puoi trovare il tuo centro dell’essere. Un uomo totale è centrato: qualunque cosa stia facendo, rimane nel centro. Se è la sua mente a funzionare, sta pensando. Il pensare si svolge nella testa, ma lui rimane centrato nell’ombelico; il centro non gli manca mai. Usa la testa, ma non si trasferisce mai nella testa. Usa il cuore, ma non si trasferisce mai nel cuore. Tutte queste cose diventano strumenti, e lui resta centrato. In secondo luogo, un uomo totale è in equilibrio. Ovviamente, quando un individuo è centrato, è anche in equilibrio. La sua vita è un equilibrio profondo e lui non è mai unilaterale, non è mai agli estremi: rimane nel mezzo. Il Buddha lo ha chiamato “la via di mezzo”. Rimane sempre nel mezzo. Un uomo che non è centrato, si sposterà sempre agli estremi. Se mangerà, mangerà molto: s’ingozzerà. Oppure può digiunare, ma per lui è impossibile mangiare nel modo giusto. Digiunare è facile, ingozzarsi va bene. Una persona simile può stare nel mondo, essere impegnata, coinvolta in esso, oppure può rinunciare al mondo – ma non può mai essere equilibrata. Non riesce mai a rimanere nel mezzo, perché, se non sei centrato non sai neppure che cosa significhi “nel mezzo”. Una persona centrata è sempre nel mezzo, mai ad alcun estremo, in ogni cosa. Il Buddha dice che il suo mangiare è un giusto mangiare: non è né ingozzarsi, né digiunare. La sua fatica è una giusta fatica: mai troppa, mai troppo poca. Qualunque cosa sia, è sempre equilibrata. Prima cosa: un individuo che abbia realizzato il Sé sarà centrato.

Seconda cosa: sarà equilibrato. In terzo luogo, se queste due cose si verificano – centratura ed equilibrio – ne seguiranno molte altre. L’individuo sarà sempre a suo agio, continuerà a essere a suo agio in qualunque circostanza. Dico qualunque sia la circostanza, senza condizioni, perché un individuo centrato è sempre a proprio agio. Anche se viene la morte, sarà a proprio agio, e la riceverà come si riceve qualunque altro ospite. Se vieni l’infelicità, la riceverà. Qualsiasi cosa accada, non può rimuoverlo dal suo centro. Anche questo essere a proprio agio deriva dall’essere centrati. Per un uomo simile nulla è banale, nulla è grande. Ogni cosa diventa sacra, meravigliosa, santa, ogni cosa! Qualunque cosa faccia, qualunque cosa, è per lui di sommo interesse: come se fosse di assoluto interesse. Nulla è banale. “Questo è banale, questo è grande”. In realtà le cose non sono grandi; e non sono neppure piccole e banali. Il tocco dell’uomo è significativo. Una persona che abbia realizzato se stessa, una persona equilibrata, centrata, trasforma tutto. Il tocco stesso rende grandi le cose. Se osservi un Buddha, vedrai che cammina e ama camminare. Se vai a Bodhgaya dove il Buddha raggiunse l’illuminazione, sulla riva della Niranjana – nel posto in cui era solito sedere sotto l’albero della Bodhi – vedrai che le orme dei suoi passi sono state segnate. Meditava per un’ora e poi passeggiava. Nella terminologia buddista questo viene chiamato chakramana. Si sedeva sotto l’albero della Bodhi, poi camminava. Ma camminava con un atteggiamento sereno, come fosse in meditazione. Qualcuno chiese al Buddha: “Perché lo fai? A volte ti siedi con gli occhi chiusi e mediti, poi cammini”. Il Buddha disse: “Stare seduti per essere in silenzio è facile, perciò cammino. Ma porto dentro di me lo stesso silenzio. Mi siedo, ma interiormente sono lo stesso, silenzioso. Cammino, ma interiormente sono lo stesso silenzioso”. La qualità interiore è la stessa…Un Buddha è lo stesso quando incontra un imperatore e quando incontra un mendicante: ha la stessa qualità interiore. Quando incontra un mendicante non è diverso, quando incontra un imperatore non è diverso: è lo stesso. Il mendicante non è insignificante e l’imperatore non è “qualcuno”: non fa distinzioni. E in realtà, incontrando il Buddha gli imperatori si sono sentiti mendicanti e i mendicanti imperatori. Il tocco, l’uomo, la qualità rimangono gli stessi. Da vivo, ogni giorno al mattino il Buddha era solito dire ai suoi discepoli: “Se avete qualcosa da chiedere, chiedete pure”. Il mattino del giorno in cui sarebbe morto avvenne la stessa cosa, chiamò i suoi discepoli e disse: “Se volete chiedere qualcosa, chiedete pure, r ricordatevi che questo è l’ultimo mattino. Prima che questo giorno finisca, io non ci sarò più”. Lui era lo stesso. Questa era la sua domanda quotidiana al mattino. Lui era lo stesso! Quel giorno era l’ultimo, ma lui era lo stesso. Proprio come in un qualunque altro giorno, disse: “Ebbene, se avete qualcosa da chiedere, chiedetelo pure, ma sappiate che questo è l’ultimo giorno”. Non c’era alcun cambiamento nel tono, ma i discepoli cominciarono a piangere. Si dimenticarono di chiedere alcunché. Il Buddha disse: “Perché piangete? Se aveste pianto in un altro giorno, non sarebbe importato, ma questo è l’ultimo giorno. Stasera non ci sarò più, perciò non perdete tempo piangendo. Un altro giorno non sarebbe importato; avreste potuto perdere tempo. Ora non perdete tempo piangendo. Perché piangete? Chiedete quanto avete da chiedere”. Era lo stesso nella vita e nella morte. Perciò in terzo luogo, l’uomo che ha realizzato il Sé è a suo agio: la vita e la morte sono la stessa cosa, beatitudine e infelicità sono la stessa cosa. Nulla lo turba; nulla lo rimuove da casa sua, dal suo essere centrato.

A un uomo simile non puoi aggiungere nulla. Non puoi togliere nulla, e non puoi aggiungergli nulla. E’ realizzato. Ogni suo respiro è un respiro realizzato: silenzioso, colmo di beatitudine: Hai raggiunto la meta. Hai raggiunto l’esistenza, l’essere. E’ fiorito come uomo totale. Questa non è una fioritura parziale. Il Buddha non è un grande poeta. Naturalmente tutto quanto dice è poesia. Non è affatto un poeta, ma è poesia persino se si muove, se cammina. Non è un pittore, ma diventa una pittura tutte le volte che parla, qualunque cosa dica. Non è un musicista, ma il suo intero essere è musica per eccellenza. L’uomo come totalità è realizzato. Perciò ora, qualunque cosa faccia o non faccia, quando è seduto in silenzio, senza fare nulla, persino in silenzio la sua presenza lavora, crea: diventa creativa. Il Tantra non si occupa di alcuna crescita parziale, si occupa di te come essere totale. Perciò tre cose sono fondamentali: devi essere centrato, radicato,equilibrato, vale a dire, sempre nel mezzo…ovviamente, senza alcuno sforzo. Se c’è uno sforzo non sei in equilibrio. Devi essere a tuo agio, a tuo agio nell’universo, a casa tua nell’esistenza, e poi molte cose seguiranno. Questo è un bisogno fondamentale perché, a meno che questo bisogno non venga soddisfatto, sei un uomo solo di nome, sei un uomo come possibilità, non lo sei realmente. Puoi esserlo; ne hai la potenzialità. Ma la potenzialità deve essere attuata.

Etichette:

Interludio Tao,

Tao Livello 3 e oltre

martedì 1 aprile 2014

il Te del Tao: LXXI - IL DIFETTO DELLA SAPIENZA

LXXI - IL DIFETTO DELLA SAPIENZA

Somma cosa è l'ignoranza del sapiente,

insania è la sapienza dell'ignorante.

Solo chi si affligge di questa insania

non è insano.

Il santo non è insano

perché si affligge di questa insania.

Per questo non è insano.

insania è la sapienza dell'ignorante.

Solo chi si affligge di questa insania

non è insano.

Il santo non è insano

perché si affligge di questa insania.

Per questo non è insano.

Etichette:

Tao

lunedì 31 marzo 2014

il Ribelle (l'Imperatore) - IV Major

La figura potente e autorevole di questa carta è evidentemente padrona del proprio destino. Sulle spalle ha un emblema del sole, e la torcia che tiene nella mano destra simboleggia la luce della sua verità, conseguita grazie a fatiche immani. Che sia ricco o povero, il Ribelle è un vero imperatore poiché ha spezzato le catene dei condizionamenti e delle opinioni della società repressiva. Egli ha dato forma a se stesso, abbracciando tutti i colori dell'arcobaleno, emergendo dall'oscurità e dalle radici informi del suo passato inconsapevole e sviluppando ali con cui volare alto nel cielo. Il suo stesso modo di essere è ribelle non perché lotti contro qualcuno o qualcosa, ma perché ha scoperto la propria vera natura ed è determinato a vivere in base a essa. L'aquila è il suo spirito animale, un messaggero tra la terra e il cielo. Il ribelle ti sfida a essere coraggioso a sufficienza per assumerti la responsabilità di ciò che sei e per vivere in funzione della tua verità.

La gente ha paura, una paura terrea di coloro che conoscono se stessi. Quegli esseri hanno un potere ben preciso, un'aura e un magnetismo, un carisma in grado di sradicare i giovani e coloro che sono vivi dalla prigione delle tradizioni. L'illuminato non può essere ridotto in schiavitù questa è la difficoltà e non può essere imprigionato, ogni genio che abbia conosciuto qualcosa della sfera interiore sarà inevitabilmente qualcosa che è difficile assimilare; sarà una forza che crea scompiglio. E le masse non vogliono essere disturbate, anche se vivono nell'infelicità; sono miserabili, ma ci hanno fatto l'abitudine. E chiunque non sia infelice sembra un estraneo. L'illuminato è lo straniero per eccellenza nel mondo: non sembra appartenere a nessuno. Nessuna organizzazione lo confina, nessuna comunità, nessuna società, nessuna nazione.

Etichette:

Tao Sincronico

e ti vengo a cercare Tao

E ti vengo a cercare

anche solo per vederti o parlare

perché ho bisogno della tua presenza

per capire meglio la mia essenza.

Questo sentimento popolare

nasce da meccaniche divine

un rapimento mistico e sensuale

mi imprigiona a te.

Dovrei cambiare l'oggetto dei miei desideri

non accontentarmi di piccole gioie quotidiane

fare come un eremita

che rinuncia a sé.

E ti vengo a cercare

con la scusa di doverti parlare

perché mi piace ciò che pensi e che dici

perché in te vedo le mie radici.

Questo secolo oramai alla fine

saturo di parassiti senza dignità

mi spinge solo ad essere migliore

con più volontà.

Emanciparmi dall'incubo delle passionicercare l'Uno al di sopra del Bene e del Male

essere un'immagine divina

di questa realtà.

E ti vengo a cercare

perché sto bene con te

perché ho bisogno della tua presenza

Etichette:

Interludio Tao

Iscriviti a:

Commenti (Atom)